The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

From Boom to Backlash: The Evolving ESG Narrative

A review of the lecture "ESG investing and the green transition" by Professor Pedro Matos 20th February 2025.

In recent years, the rise of ESG investing has been both lauded as a financial revolution and criticized as a marketing ploy. The movement, which initially sought to align capital markets with sustainable outcomes, has faced mounting scrutiny over whether it genuinely drives meaningful change particularly on the “E” dimension of ESG. In the latest seminar from the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, Professor Pedro Matos delivered an evidence-based assessment of ESG investing’s role in the green transition—separating hype from impact.

Just a few years ago, 2021 was hailed as the “year of ESG”, with record capital inflows into sustainable funds and mounting regulatory support. However, by 2023, a wave of skepticism emerged—driven by accusations of greenwashing, political backlash, and regulatory scrutiny. By 2025, the pushback deepened, with asset managers pulling back from climate alliances. At the same time, progress on the green transition exceeded expectations with the rise of renewable energy and electrical vehicles. What do these mixed signals mean for investors and policymakers? Matos framed the evolution of ESG investing into three distinct phases: ESG 1.0, questioning whether investors truly integrate ESG principles into their portfolios; ESG 2.0, addressing whether ESG actions actually result in meaningful environmental impact; and ESG 3.0, focusing on whether ESG investing accelerates the green transition through the ramp up of measurable corporate green revenues.

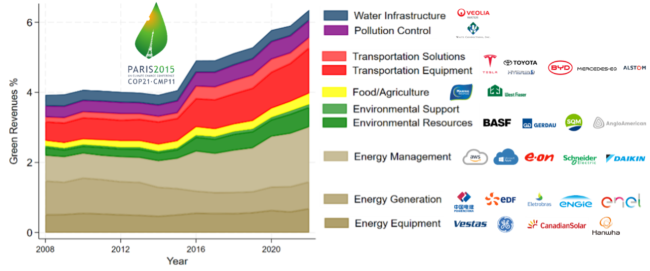

A crucial part of Matos’ lecture focused on measuring the actual size of the green economy—not by ESG scores, but by corporate revenues derived from products and services that contribute positively to the environment. Using the LSEG FTSE Russell’s Green Revenues Classification System (GRCS), his research finds that green revenues have grown from 4% to 6.5% of total corporate revenues post-Paris Agreement. In 2022, the global green economy was valued at $4 trillion, roughly equivalent to the oil and gas sector. Green revenues are heavily concentrated in Europe, where policy frameworks like the EU Taxonomy have pushed firms towards sustainable business models. Green revenue leaders include players like Tesla or BYD in transportation utilities such as Electricite de France or Veolia and manufacturers such as Schneider Electric.

The Growth of Corporate Green Revenues

This graph plots the percentage of green revenues by each of the 10 GRCS green business activities relative to total revenues per year. Source: Figure 1 of Klausmann, Krueger & Matos (working paper, 2025) “The Green Transition: Evidence from Corporate Green Revenues”

Matos’ research identifies two primary drivers of corporate green growth. The first is technological innovation, measured through green patents[1]. Firms with significant green patent portfolios before the Paris Agreement saw a 2.3% increase in green revenues after the agreement, with this effect being most pronounced in U.S. firms that were better able to commercialize green innovations. The second driver is institutional investment, particularly from ESG-aligned funds. Firms with high ownership by PRI signatories, climate-focused CDP members, and long-term institutional holders saw higher green revenue growth, suggesting that some ESG investors do contribute to the transition—but only under the right conditions.

The UN-sponsored Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) today represents more than $120 trillion in assets. The PRI framework encourages investors to incorporate ESG considerations into their financial models, engage with portfolio companies, and report annually on sustainability progress. Matos highlighted the diverse approaches taken by PRI signatories, ranging from exclusionary screening and thematic investing to more proactive corporate engagement. While European institutional investors lead in ESG integration, their U.S. counterparts exhibit a more cautious stance, often prioritizing financial risk over sustainability objectives. Evidence suggests that PRI signatories generally hold better ESG-scoring stocks than non-signatories, but this trend is not observed for U.S.-based ones.[2]

One of the most contentious questions in sustainable investing is whether green stocks outperform legacy firms. Matos’ research tests whether firms with high green revenues generate excess returns, or “green alpha,” after controlling for standard risk factors. The findings show that green stock portfolios (firms with more than 50% green revenues) outperformed post-Paris Agreement, but this outperformance was heavily concentrated in the U.S., largely driven by companies such as Tesla and other green “pure plays”. European green stocks did not experience the same financial gains, suggesting that while regulation fosters green growth, it does not necessarily maximize investor returns.

Another major theme in the lecture was the difference between tilting portfolios towards green assets versus actually driving the green transition. While many ESG funds have reduced their exposure to high-carbon firms, this approach does not necessarily reduce global emissions. Institutional investors now hold a larger share of global market capitalization, but their carbon footprints have remained flat. This suggests that funds are “greening their portfolios” by selling brown assets rather than engaging companies to decarbonize. Only 10% of global industrial emissions reside in public equities, meaning that exclusionary ESG strategies do not address the vast majority of emissions.[3]

Matos concluded with a discussion on the broader implications of his findings. The evidence suggests that the green transition is progressing, but at a pace that may not meet climate goals. Investors should focus on green revenues rather than relying solely on ESG scores. Divestment alone is insufficient—active engagement is needed to drive decarbonization. Regulation shapes market behavior but does not guarantee returns, and green incentives must align with financial viability. As we enter ESG 4.0, Matos suggests that the next frontier may be AI and climate tech convergence—a potential game-changer in scaling sustainable solutions. Yet, one big open research question is whether AI will ultimately “ruin” or “save” the planet. With so many uncertainties, one thing is clear: for ESG investing to maintain credibility and effectiveness, it should evolve beyond metrics and labels to deliver tangible, system-wide change.

.............................................................

[1] Data comes from UVA Darden Global Corporate Patent and the classification of green patents based on the Hascic & Migotto (OECD, 2015) classification.

[2] Gibson, Glossner, Krueger, Matos and Steffen (Review of Finance, 2022) “Do Responsible Investors Invest Responsibly?”

[3] Atta-Darkua, Glossner, Krueger & Matos (working paper, 2024) “Decarbonizing Institutional Investor Portfolios: Helping to Green the Planet or Just Greening Your Portfolio?”

-----------------------------------

This lecture is part of the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, a global initiative on sustainable business. Nanyang Business School (NBS), in collaboration with the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI), launched this series to foster knowledge exchange between academics, practitioners, and policymakers. As part of this initiative, leading academics present cutting-edge research on sustainability topics, while industry experts moderate discussions, providing real-world insights and facilitating dialogue between research and practice.