The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Cracking the Green Code: Designing Smarter Sustainable Debt

The Green Financing Challenge

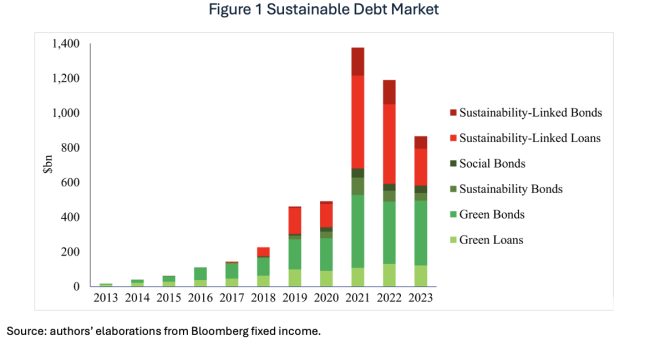

Financial markets are playing an increasingly important role in the fight against climate change. Despite the rising interest rate environment contributing to a recent slowdown, the sustainable debt market has grown exponentially over the past decade, surpassing $7.5 trillion as of 2023 or 5 percent of the global bond market[1]. This growth has been marked by an increase in the types of debt securities on the market, as well as heightened concerns regarding greenwashing and the limited environmental impact of these securities[2]. A recent paper, The Optimal Design of Green Debt by Adelina Barbalau and Federica Zeni, develops a theoretical framework for understanding how to structure debt contracts to curb greenwashing while maximizing environmental outcomes.

Understanding the Sustainable Debt Landscape

Despite the proliferation of securities in the sustainable debt market, a distinction can be made between two underlying contract designs:

- project-based designs, such as green bonds (GBs), which focus on specifying tangible projects that the proceeds are going to be allocated to, without targeting specific environmental outcomes

- outcome-based designs, such as sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), which do not impose restrictions on the use of proceeds but focus on outcomes by linking the cost of debt to the achievement of environmental targets

The fact that GBs focus on actions (i.e., implementation of green project) rather than outcomes (i.e., carbon reductions) does not ensure nor does it incentivize the achievement of environmental goals. However, the fact that SLBs focus on green outcomes which cannot be measured precisely and are prone to manipulation, along with their lack of transparency regarding the use of proceeds, raises a distinct set of challenges.

Designing Green Debt Optimally

The paper “Optimal Design of Green Debt” takes a closer look at the development of the sustainable debt market to uncover what are the trade-offs and inefficiencies involved in issuing GBs or SLBs and, importantly, how securities aimed at financing the provision of green outcomes should be optimally designed. The authors consider a setup in which green outcomes can be obtained through the implementation of tangible green projects (e.g., solar panels) and/or intangible effort-based strategies (e.g., reducing energy consumption) and which allows for greenwashing, defined as the possibility to manipulate reported outcomes. They incorporate these features into a principal-agent problem in which an investor (principal) with pro-environmental preferences provides debt financing to a profit-maximizing firm (agent). The model delivers the following main results:

1. When greenwashing is not possible

If green outcomes are precisely measurable, an outcome-based instrument (like SLBs) is ideal. These instruments incentivize firms to pursue both tangible projects (e.g., solar panels) and effort-based strategies (e.g., energy efficiency), achieving efficient outcomes.

2. When greenwashing is very likely

If firms can easily manipulate reported green outcomes, the optimal contract takes the form of a project-based instrument (like GBs). Since reported outcomes cannot be trusted, the only reliable solution is funding tangible projects with environmental potential.

3. When greenwashing is possible but costly

When manipulation is possible at a cost, the optimal contract is a hybrid combining both project- and outcome-based features. Specifically, it includes a payoff component that depends on the environmental outcomes achieved, and a payoff component that depends on the implementation of green projects, i.e. the use of proceeds. Whereas the role of the outcome-dependent payoff is to incentivize effort-based strategies while controlling for manipulation, the role of the project- dependent payoff is to ensure that proceeds are allocated to the right projects.

Empirical Relevance and Market Implications

In practice, the theoretically optimal hybrid contract—combining pay-for-performance with dedicated use-of-proceeds—is rarely observed in the market. However, several issuances align with this design. For instance, the Austrian utility company Verbund issued a green and sustainability-linked bond in 2021 that integrates periodic reporting on performance targets with updates on projects funded by the proceeds (Verbund, 2012). Importantly, ICMA recently released guidelines for the issuance of Sustainability-Linked Loan financing Bonds - hybrid instruments that combine use-of-proceeds features with sustainability targets - signaling a market shift toward hybrid structures that reflect the optimal theoretical design.

The limited adoption of hybrid contracts can be attributed to the complexity and costs of contracting on multiple dimensions, as well as the associated monitoring and reporting requirements, making simpler instruments like GBs and SLBs the dominant options. The paper formally characterizes the inefficiencies of these two contracts, pins down the sources of such inefficiencies, and rationalizes issuance patterns across industries. For instance, through the lens of the model, financial institutions primarily issue GBs because the green outcomes they can deliver, e.g., Scope 3 emission reductions, are highly imprecise and prone to manipulation. Utilities, on the other hand, favor GBs due to their access to tangible projects and limited scope to improve their environmental performance through effort-based strategies.

Policy Implications

The effectiveness of financial market solutions for combating climate change depends on well-designed contracts that align incentives, foster accountability, and curb manipulation. The findings highlight that when greenwashing is possible, the security designs prevalent on the market (GBs, SLBS) are likely to be inefficient, and a hybrid design that combines transparency about use of proceeds with accountability to outcomes is best. Improvements in measurement systems, green lending policies as well as the development of more rigorous reporting and verification standards play a crucial role in ensuring the integrity and growth of the market. Policymakers, investors, and firms must ultimately work together to ensure that sustainable finance lives up to its promise of driving meaningful environmental change.

..............................

[1] Source: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA).

[2] The volume has dropped between 2021 and 2023, reflecting broader trends in global debt markets (source: IMF, 2023) ; however the growth over a ten year period remains substantial.

_______________

By Adelina Barbalau (University of Alberta) and Federica Zeni (World Bank)

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.