The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Breaking the thermometer does not hide the fever

A review of the lecture ‘Double materiality, underlying ethical principles for investing, and performance’ by Professor Rodolphe Durand 17th April 2025.

It’s one thing to argue that firms should account for their impact on the environment and society. It’s another to show that the market already does. In a nuanced and empirically rich lecture delivered as part of the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, Professor Rodolphe Durand (HEC Paris) stepped away from the now-familiar moral and philosophical case for double materiality to examine what boards, markets, and capital providers are actually doing when faced with systemic risks that traditional risk-return models fail to capture.

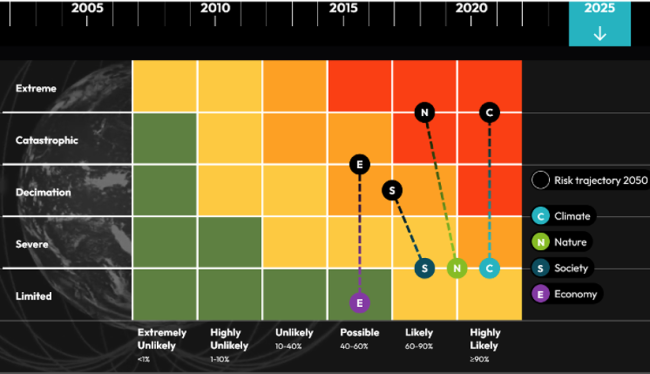

Durand began by outlining a growing disconnect between macro-level environmental crises and firm-level risk modelling. Planetary boundaries are not reversible, he noted, and yet our valuation techniques assume linearity and equilibrium. Still, rather than dwelling on conceptual critiques, he moved on to explore emerging institutional responses—offering what amounted to a guided tour of how financial actors are internalizing non-linear, non-firm-specific risks.

For instance, a study by Caroline Flammer, Michael Toffel, and Kala Vismanathan finds that environmental shareholder proposals drive a 4.6% increase in climate risk disclosures, with affected firms experiencing positive valuation effects. Markets are not neutral observers in this transition—they reward transparency and foresight. Similarly, climate-related litigation has been shown to produce immediate market penalties, with the mere filing of lawsuits reducing firm valuations and triggering ripple effects across related sectors. The market is no longer waiting for verdicts. Litigation has become a signal of future liabilities and reputational exposure—pushing firms to proactively embed environmental risk into governance systems.

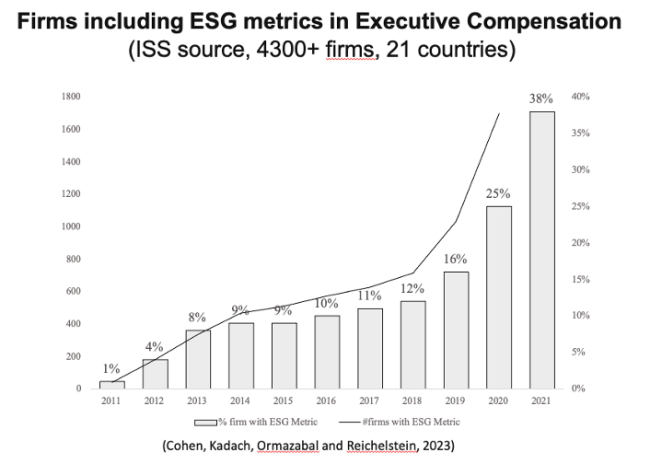

Boards are beginning to respond. According to a 2023 cross-country study by Cohen, Kadach, Ormazabal, and Reichelstein, over 38% of large companies have now incorporated ESG metrics into executive pay packages. These range from emissions targets to supply chain oversight and social impact indicators. While some observers remain skeptical of 'greenwishing'—the selective use of sustainability language to appease stakeholders—Durand emphasized that incentive-linked ESG governance is increasingly being tied to hard performance metrics, particularly in sectors facing investor pressure and regulatory scrutiny.

In the banking sector, pricing signals offer further evidence that systemic risk is being internalized. Firms with board-level climate oversight—such as sustainability committees or designated ESG officers—benefit from lower loan spreads and lighter covenant packages. These findings, based on DealScan loan data, underscore a new logic in credit underwriting: climate resilience is credit-enhancing, and governance structures that mitigate exposure to ecological shocks are being rewarded with capital.

Meanwhile, research by Xia Li, published in the Strategic Management Journal, shows that firms with formal climate governance structures are more agile in responding to operational shocks, from floods to supply chain disruptions. ESG governance, in this case, becomes not just a reputational shield but an operational asset.

Durand did not claim that these examples amount to systemic transformation. But taken together, they suggest that a plural, double materiality-informed definition of performance is being trialed—quietly, iteratively, and in sectors where long-duration capital is sensitive to macro fragility. The recent 2025 “Planetary Solvency” report issued by global actuarial associations warns that escalating climate and biodiversity risks may render entire industries uninsurable within decades.

What’s shifting, Durand argued, is not just what gets measured, but how we model causality and accountability. The ecological fallacy—drawing firm-level conclusions from aggregate trends—has long distorted how we think about strategic value. But so too has its inverse: assuming that optimizing individual firm returns will produce collectively sustainable outcomes. The empirical evidence suggests this assumption is breaking down. Markets and governance institutions are responding—messily, incompletely, but unmistakably.

These ideas are explored more fully in Durand’s recent co-authored paper, “Strategy Can No Longer Ignore Planetary Boundaries: A Call for Tackling Strategy's Ecological Fallacy,” which argues for integrating planetary boundaries into core strategic management frameworks.

Durand’s closing remarks circled back to the idea that performance is a moral construct, embedded in social norms, institutional logics, and scientific constraints. Double materiality, in his telling, is not just a regulatory invention. It is a reflection of shifting boundaries—both environmental and epistemological. For boards and investors, the task ahead is not to choose between financial and systemic reasoning, but to build models, metrics, and mandates that can hold both in view.

-----------------------------------

This lecture is part of the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, a global initiative on sustainable business. Nanyang Business School (NBS), in collaboration with the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI), launched this series to foster knowledge exchange between academics, practitioners, and policymakers. As part of this initiative, leading academics present cutting-edge research on sustainability topics, while industry experts moderate discussions, providing real-world insights and facilitating dialogue between research and practice.