The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Public markets are losing significance: The Blurring Lines Between Private and Public Ownership

A review of the lecture "The Blurring Lines Between Private and Public Ownership" by Prof. Michelle Lowry on 9th January 2025.

In recent years, the corporate landscape has undergone a subtle but profound transformation. The once-clear distinction between private and public companies is dissolving, as private firms increasingly adopt the characteristics of their public counterparts. In a compelling lecture as part of the ECGI - Kelley School of Business’ Institute for Corporate Governance and Ethics (ICGE) Spring 2025 Speaker Series, Michelle Lowry, Professor of Finance at Drexel University and a leading voice in corporate finance, explored the evolving nature of firm ownership, capital sourcing, governance structures, and investment dynamics. Her research, recently published in the Handbook of Corporate Finance, explores the effects of firms staying private longer; the shift raises fundamental questions about investor access, transparency, and corporate governance.

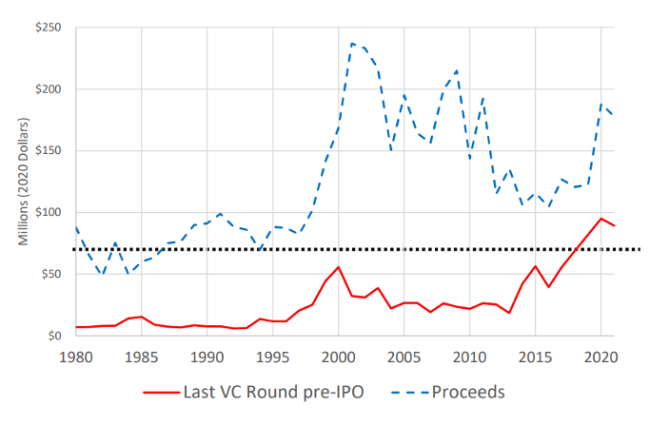

At the heart of this shift is a paradox. While the number of publicly listed companies has dwindled, the number of private firms has surged. Yet, many of these private firms are far from the small, closely held entities that once defined the category. Instead, they exhibit public-company traits—receiving substantial capital from institutional investors, expanding their governance structures, and engaging in acquisitions. The median size of the final venture capital round before an IPO has skyrocketed, reaching levels comparable to IPO proceeds in the 1990s. Mutual funds and hedge funds—historically confined to public markets—now routinely invest in private firms, further blurring the lines.

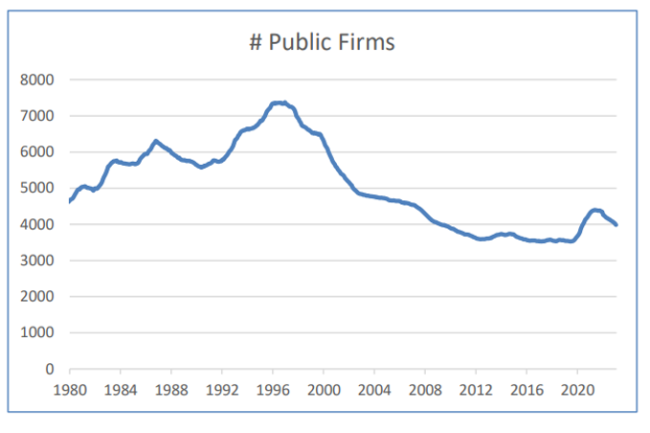

In 1997, there were approximately 7,374 public companies in the U.S. This figure has since declined to around 4,335 as of 2021. The trend signals a shift in corporate financing strategies, with firms increasingly choosing to stay private for longer. (Slide 4).

The reasons firms choose to remain private longer are multifaceted. First, the availability of capital has dramatically shifted. Whereas firms once had to tap public markets to fund growth, today’s capital-rich environment allows them to raise vast sums privately. Second, confidentiality concerns loom large. A greater portion of firms belong to R&D-intensive industries, and these firms prefer to avoid public disclosure requirements that could expose their strategies to competitors. Third, regulatory requirements have increased, and this may make public listing a less attractive option.

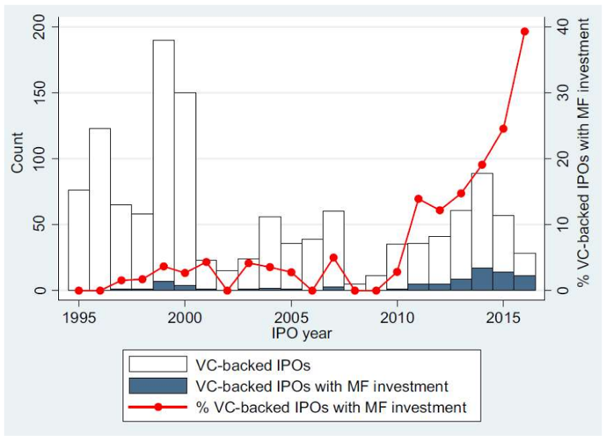

By 2017, nearly 40% of VC-backed IPOs had mutual fund investment prior to going public, a striking shift from less than 5% before 2010 (Slide 14).

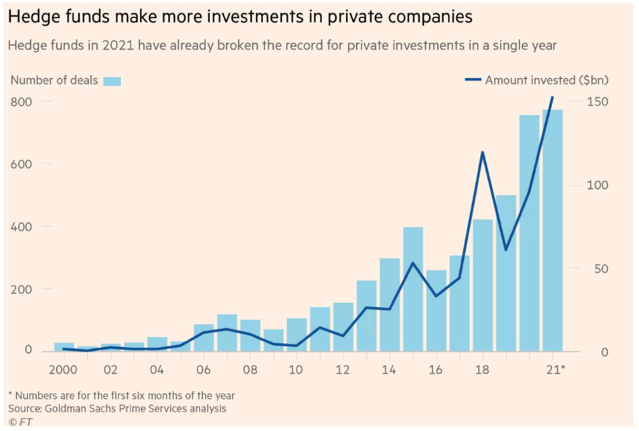

Similarly, hedge funds have followed suit, increasing their stakes in high-growth private firms (Slide 16).

But while the benefits of staying private are clear, the implications are more complex. From a market structure perspective, private equity does not provide the traditional advantages of public markets—broad investor access, transparency, and governance accountability. From an investor perspective, investors who are mostly constrained to investing in public firms, for example pension funds and retail investors, find themselves with fewer viable investment opportunities.

Late-stage private firms frequently raise capital exceeding $100 million, an amount similar to median IPO proceeds in the 1990s (Slide 18). Additionally, many late-stage private firms now have dispersed investor bases, including mutual funds, hedge funds, and other institutional investors (Slide 22, not shown).

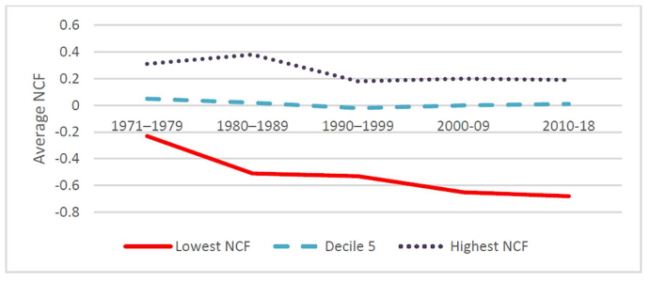

Public firms are increasingly characterized by high negative Net Cash Flows which makes it harder to assess the ‘true value’ of such firms. (Slide 28)

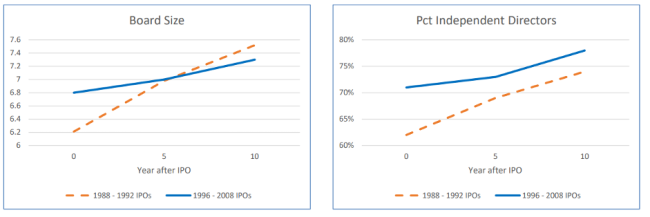

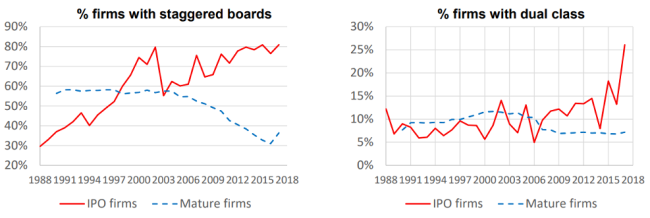

Among the firms choosing to stay private longer, we see significant changes in governance structures. First, private firms are increasingly adopting independent directors and larger boards, reflecting their growing complexity. When these firms do go public, governance transformations are less dramatic than in previous decades. Second, many firms now go public with staggered boards and voting structures that allow founders to retain disproportionate control—raising concerns about long-term accountability. In sum, the evidence challenges the traditional view that governance structures shift abruptly at IPO. Instead, governance changes occur gradually, beginning years before a firm goes public and continuing long afterward.

The percentage of private firms with independent directors has steadily risen, from 37% at the first financing round to 65% by the fourth round (Slide 38, not shown). Compared to firms that went public in the 1980s, modern IPO firms already have larger boards and greater board independence at the time of listing, meaning post-IPO governance changes are less pronounced (Slide 40).

In one quarter of PE-backed IPOs, pre-IPO investors still hold 30% or more of shares six years post-IPO (Slide 24, not shown) and the use of dual-class shares and staggered boards has surged, allowing founders to maintain decision-making authority (Slide 42).

The increasing maturity of firms at the time of the IPO means that many governance improvements—such as independent boards—occur before firms transition to public status. This shift in corporate structure has far-reaching consequences. Public companies face intensifying competition from well-capitalized private firms that operate with fewer regulatory constraints. Investors must navigate a changing landscape where access to high-growth companies is increasingly limited to those able to participate in private markets. Regulators, meanwhile, are grappling with whether existing frameworks adequately address the realities of modern corporate finance.

One of the lecture’s most thought-provoking insights was the impact of these changes on firm strategy. Traditionally, firms relied on organic growth before going public, with acquisitions accelerating post-IPO. Today, however, private firms are pursuing inorganic growth at a far greater rate than in the past. Macroeconomic factors—globalization, economies of scale, and the shift towards intangible assets— reward size and market dominance and thus push firms to grow rapidly. The greater availability of private capital has enabled firms to achieve such growth without going public. These firms acquire competitors and expand aggressively while remaining private, fundamentally altering market dynamics.

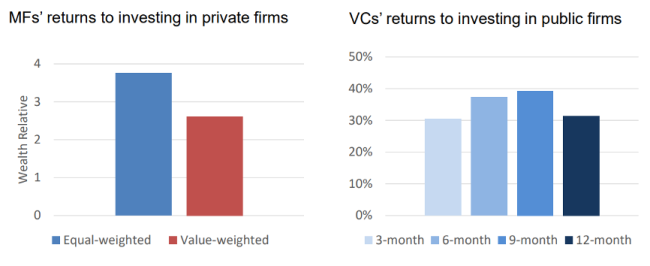

Mutual funds investing in private firms have earned 2.5 – 3.7 times as much as they would in a market-wide index, while venture capitalists investing in public firms post-IPO have secured 30 – 40% abnormal returns (Slide 31).

As firms evolve, so too must the strategies of investors, regulators, and policymakers. The traditional life cycle of a firm is no longer a given. Instead, we see a spectrum where private and public status is fluid, shaped by the availability of capital, governance considerations, and strategic incentives. This evolution requires new thinking about investor protections, regulatory oversight, and the long-term implications for capital markets.

Michelle Lowry’s research provides a roadmap for understanding these shifts. As private firms increasingly resemble public companies—and public firms adopt governance structures that consolidate insider control—the distinctions between these categories may become more theoretical than practical. The key question, then, is not whether firms should be public or private, but how to ensure that corporate governance and market access evolve in a way that serves all stakeholders. For investors, this means reflecting on how and where to deploy capital. For regulators, it requires balancing oversight with the flexibility needed to accommodate a changing market. And for corporate leaders, it presents both a challenge and an opportunity: to navigate an era in which the very definition of corporate ownership is being rewritten.

-----------------------------------

This lecture is part of the Indiana University - ECGI Online Series, a public lecture series on corporate governance. The Kelley School of Business Institute for Corporate Governance (ICG+E), in partnership with Ethical Systems, collaborates with ECGI to deliver this ongoing initiative. As part of this public lecture series, distinguished speakers share insights on the evolving landscape of governance, finance, and market regulation.

To download the presentation slides, click here.