The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Half the Firms, Twice the Profits: American Public Firms’ Transformation, 1996-2022

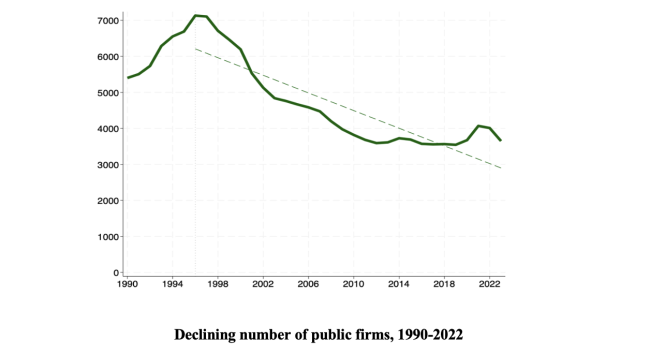

The number of public firms in the United States has nearly halved since 1996, causing consternation among some corporate leaders and securities law regulators.

Representative analyses plead for a “wake-up call for America” because of a “decimation of the U.S. capital markets structure [and a] demise of the IPO market,” that led to “the systemic decline in the number of publicly listed companies.” Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan Chase’s CEO, lamented in his 2023 JPMorgan Chase letter to shareholders the “shrinking public markets” and the “diminishing role of public companies. . . . From their peak in 1996 at 7,300, U.S. public companies now total 4,300. . . . The trend is serious. . . . Is this the outcome we want?” Those who lament the decline in number since 1996 often bring forward over-regulation as a central cause, as did Mr. Dimon. This perspective of decline, with regulation a primary cause, has become a standard narrative in important circles. But a look at the overall changes in the American public firm sector should make us hesitant of accepting that narrative.

The basic fact that corporate leaders, such as Jamie Dimon, and many regulators worry about—a sharply declining number of public firms—is accurately reported. The figure below shows the decline in number from more than 7,000 in 1996 to fewer than 4,000 in 2022.

The dominant explanations, often advanced by Securities and Exchange commissioners when considering policy initiatives, come from over- or under-regulation of the stock market. The central legal explanation is that the heavy burden of corporate and securities law has made the cost of being public too high. Conversely, goes the second legal explanation, capital-raising rules for private firms were once very strict but have loosened up. Private firms can now raise capital nearly as well as small- and medium-sized public firms. Private firms are displacing public ones. Either way, these views see legal imperatives as explaining the sharp decline in the public firm.

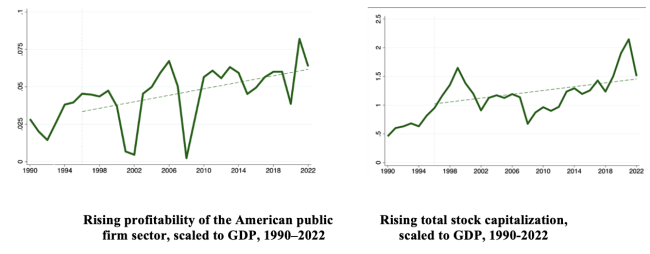

We challenge the implications of this thinking. While the number of firms nearly halved, public firms’ economic weight has not halved. To the contrary, the public firm sector has held steady by every other measure for the past quarter-century that we examine. For several central qualities, the American public firm sector has become much bigger: profits are up greatly over the past three decades, the market value of the public sector is also up greatly, and revenue, investment, and employment have all kept up with the economy’s growth. In fact, net income and stock market capitalization have grown much faster than the economy, with revenues and investment keeping up with its economy’s growth. The next two figures show the rise in net income and the rise in stock market capitalization of the public firm sector, scaled to GDP. Compare their rising trendlines to the declining number of firms in the first figure above.

We emphasize that the far fewer firms are producing more net income not less. At the profit rise’s peak in 2021 public firm income was double that of 1996 profits, amounting to 6% of the country’s GDP. This rise in income has not been stressed in prior work looking at the declining number of public firms.

The rise in net income amounts to $1 trillion in current value—a very big number, equal to several percent of GDP. Moreover, it would be a mistake to dismiss this profit and stock market capitalization trend as due to the enormous success of the FAANG companies (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google) and others. The public firm sector outside of the FAANG companies, and indeed outside of the S&P 500, have grossly diminished in the number of public firms, but not in profit or stock market capitalization.

These results are not artifacts of particular profit conceptualizations. The major conceptualizations of profit show results rising or steady: profit before extraordinary items, pre-tax profit, and economic profit.

This rise in net income as a proportion of American GDP has implications about what really is happening in the public firm sector, which is the second challenge we raise: does the explanation for the changing configuration of the public firm sector lie primarily in corporate and securities law’s burdens? The rise in net income cannot be readily explained by changes in securities regulation and corporate law. And in other policy circles—at the Federal Trade Commission or the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, for example—policymakers ask why American industry is so much more concentrated now, with fewer firms in most industries today than there were at the end of the twentieth century. Yet these policymakers—and their academic correlates—bring forward efficiency, industrial organization, and sometimes antitrust explanations, not corporate or securities regulation. Little crossover exists between these two policymaking circles, one focusing on corporate and securities regulation (the SEC) and the other on competition (the FTC). We explore real economy changes that could readily explain the reconfiguration of the American public firm sector to one that is more profitable, more valuable, and with bigger but fewer firms.

These real economy developments largely tie to industrial organization via changes in the efficient scope and size of the firm (according to much academic analysis) or perhaps to changes in antitrust enforcement (according to common progressive political views). In a single article, this explanatory effort can only be exploratory. We build a baseline: There are fewer firms, but the firms are much more profitable, bigger, and often in more concentrated industries. It’s plausible that these two trends are connected—part of the same transformative phenomenon. Our purpose is not to reject the general relevance of the regulatory thesis, but to show its limits. We show why the legal explanation is unlikely to be the complete story for the package of changes over the past quarter-century of the American public firm sector and plausibly it’s not even the most important one. Corporate policymakers should adjust appropriately.

A short summary of the papers "Half the Firms, Double the Profits: Public Firms' Transformation, 1996-2022" appeared in the Wall Street Journal.

______________________

By Mark J. Roe (Harvard Law School) & Charles C.Y. Wang (Harvard Business School)

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.