Practicing Systematic Stewardship

Issue 3 | April 2023

Greetings from Brussels,

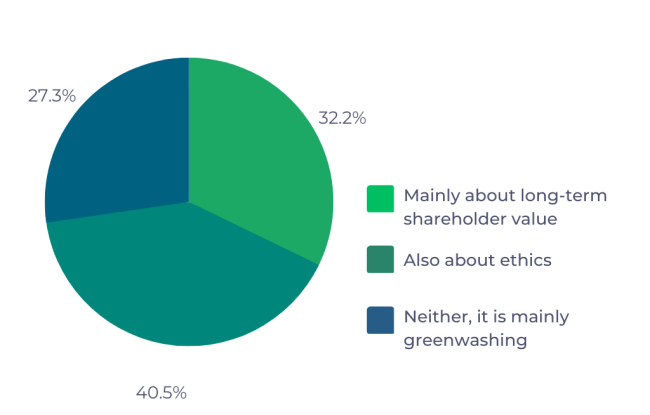

Last month I explored the term ‘ESG’ and asked readers how you understand it – and many of you answered. While there was a slight preference for the ‘ethical ESG’ interpretation, the results of the poll reflect the deviating viewpoints rather well.

Given the rising controversies surrounding this ideologically charged term, it does not come as too big of a surprise that BlackRock’s CEO Larry Fink did not mention ESG once in the recent edition of his ‘annual letter’.

Sustainability risk and the transition to a low carbon economy are still themes in the letter, but contrary to previous editions they are presented in a more restrained manner. The same can be said for the asset manager’s stewardship approach, stating that ‘as minority shareholders, it’s not our place to be telling companies what to do’ and it is ‘not our role’ to ‘engineer a particular outcome in the economy’.

The broad sustainability claims contained in previous letters from Mr. Fink always faced some skepticism. Yet there are a number of theories that serve as an explanation as to why BlackRock would want to engage on sustainability in the first place.

Broadly diversified asset managers, such as BlackRock, Vanguard or State Street, are perceived as ‘universal owners’, meaning they manage an economy-mirroring portfolio of assets. This makes their portfolio vulnerable to economy-wide risks. Not least among them, the effects of climate change which will have disastrous effects on our world’s economy.

These risks are too widespread to be diversified away, leaving portfolios mirroring large parts of the economy heavily exposed. It is therefore in the asset managers’ own interest to ‘internalize intra-portfolio negative externalities through climate change related activism’.

This appears to be at odds with the assumption that large diversified funds have little incentives to engage with investee companies. Yet there is a difference between ‘idiosyncratic stewardship’ and this ‘systematic stewardship’, where the motivation derives from a portfolio-level rather than firm-level view.

Systematic stewardship argues that large diversified funds do have an interest in engineering a particular outcome in the economy, namely one which benefits their portfolio’s profitability in the long run. In order to achieve this goal they may engage with specific companies or industries in a manner that can potentially be detrimental to individual companies’ profits, as long as it benefits the overall portfolio over time. The risks which the stewards want to reduce can be climate change risk, but also social stability risk or systemic risk arising from the financial sector. An asset manager may for example prefer to sacrifice some of a bank’s profitability in favour of stability, to avoid bank failure and contagion throughout the economy.

Climate risk is very complex and entire industries contribute to it. Divesting from highly-emitting companies may remove them from an investor’s portfolio, but it does not restrain the economy-wide risks. One way out of this predicament for the asset manager is to encourage investee companies to fade out practices that heavily contribute to climate change.

While asset managers may be less vocal about this approach in 2023, they still have good reason to practice systematic stewardship. This invites some cautious optimism. Yet it is important to note that systematic stewardship is not based on altruistic motives. Asset managers only address systematic risks to serve the ultimate goal of portfolio-wide value creation. Many sustainability or ESG topics do not constitute systematic risks. Even if asset managers successfully practice systematic stewardship they are therefore still far from addressing many other societal challenges.

What do you think? Let us know by sharing your thoughts in the survey below.

Cordially yours,

Marleen

MINI POLL...

Indicate which of the following statements you agree with most:

A) Investors are not positioned to meaningfully affect climate change

or other systemic risks

or

B) Investors have an important role to play in addressing climate risk and

other systemic issues at individual companies

Marleen Och is a PhD researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium. She works in the field of sustainable finance and corporate governance, writing about shareholder engagement and sustainability.

Please feel free to get in touch, share your thoughts and let us know how we're doing, email Marleen.Och@ecgi.org and follow us on Twitter at @ecgiorg