CSDDD – Too big to fail? March 2024

Issue 11 | March 2024

Greetings from Brussels.

If, like me, you work in a field related to corporate governance and/or the EU bubble, you likely did not make it through the last few weeks without reading about the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

The CSDDD or CS3D, whose name is a prime example of the EU’s notorious use of acronyms, is a Directive on corporate sustainability due diligence. It came to fame in recent weeks thanks to some House-of-Cards-worthy political drama .

Although the Council and European Parliament had already reached a provisional agreement in December, a number of countries withdrew their support last-minute, forcing the negotiations to reopen. The vote was rescheduled several times and serious concessions had to be made to push the file closer to the finish line, which is the final Parliament vote in April.

The most notable last-minute changes concern the narrowed down scope and the delayed implementation dates to 2027-2029. The Directive will now only apply to companies with a turnover of €450 million and a threshold of 1000 or more employees, thereby only covering 0.05% of EU companies and 70% less than what had been previously agreed on.

As much as I would enjoy voicing all my frustration about the disservice such political power-play does to the reputation of the EU’s democratic institutions, I believe you are better served with an analysis of the substance of this legislative file and how it transformed over the time of its genesis.

Let’s recap.

The proposed CSDDD is the outcome of the EU’s sustainable corporate governance initiative, which had started out as a project to align companies’ interests with those of its management, shareholders, stakeholders and wider society. By also incorporating corporate due diligence obligations along global supply chains, the EU merged two adjacent legislative ideas.

The Commission’s CSDDD proposal was already tilted towards the due diligence aspects, but also contained a number of corporate governance elements, of which I want to highlight a few.

The first of those highly contested provisions concerned directors duties and would have explicitly added sustainability matters, such as human rights, climate change and environmental consequences to the directors’ general duty of care.

Directors would furthermore have the responsibility to establish, implement and supervise the companies’ due diligence policies. I discussed the benefits of such a director oversight duty in Issue #8 – Does it (still) pay off to pollute.

The proposal also required certain companies to link parts of the directors’ remuneration to their contribution to the company’s business strategy and long-term interests and sustainability. Linking executive compensation to sustainability metrics in a meaningful way can be challenging and the empirical evidence on its results provides us with a mixed picture.

At a certain point in the negotiations there was even an article introduced that encouraged shareholder engagement on ESG topics, something I had been particularly interested in, given the striking absence of shareholder concerns in the proposal.

How many of these corporate governance aspects made it into the (almost) final text you may wonder? The answer is: none.

What started out as a ‘sustainable corporate governance’ initiative ended up being anything but that.

Regardless, the CSDDD is still groundbreaking, not only for the way people fought to prevent it from failing, but also for the shift in strategy it represents. Unlike many other corporate sustainability rules, the CSDDD does not just mandate disclosure, but actual operational changes. Companies will be required to implement measures to prevent, identify, and mitigate adverse impacts on human rights or the environment arising from their own operations, subsidiaries and business partners. Furthermore, they have to develop a plan and actually align their business model with the Paris Agreement's objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Unlike many disclosure rules, CSDDD comes with its own set of sharp teeth in the form of dedicated supervisors as well as civil liability and access to justice provisions.

Instead of bemoaning the corporate governance loss, we might want to view this outcome as an opportunity to address sustainable corporate governance in a fresh context. In fact, it is a topic so vast and important it might be better served by treating it on its own, rather than squeezing a few provisions into the CSDDD.

What do you think? Let me know in the poll below.

Cordially yours,

Marleen

MINI POLL

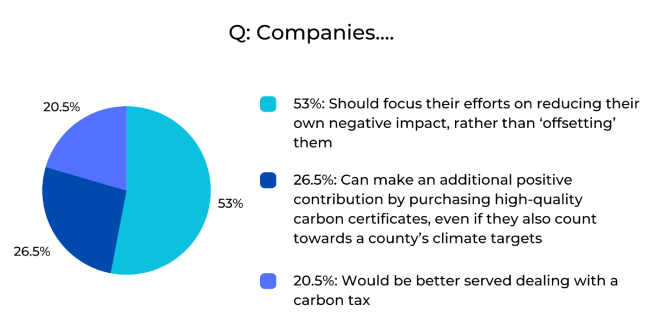

LAST MONTH'S POLL RESULTS...

PREVIOUS ISSUES...

In Focus Newsletter

Issue #10 - Compensate or abate? (February 2024)

Issue #9 - CEO Activism (January 2024)

Issue #8 - Does it (still) pay off to pollute? (November 2023)

Issue #7 - Mind the Gender (Eco) Pay Gap (October 2023)

Issue #6 - KPop or Meme Stock (September 2023)

Issue #5 - Exit or Voice? Time to take stock (June 2023)

Issue #4 - Controlling Shareholders (May 2023)

Issue #3 - Practicing Systematic Stewardship (April 2023)

Issue #2 - The Who, What and Why of ESG (March 2023)

Issue #1 - Responsible Capitalism (February 2023)

Marleen Och is a PhD researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium.

She works in the field of sustainable finance and corporate governance, writing about shareholder engagement and sustainability.

Please feel free to get in touch, share your thoughts and let us know how we're doing, email Marleen.Och@ecgi.org and follow us on Twitter at @ecgiorg