Controlling Shareholders

Issue 4 | May 2023

Greetings from Brussels,

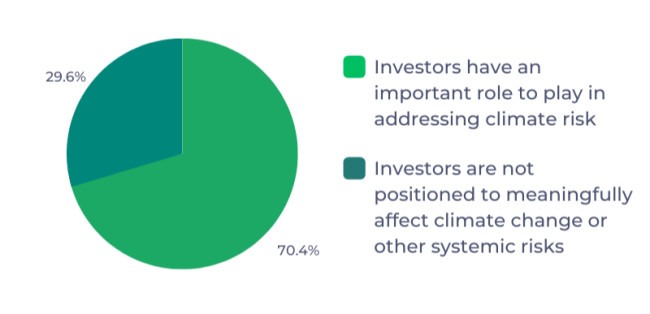

Last month I followed the divisive debate on systematic stewardship and the role of large diversified funds, which many of you view as quite crucial:

In this newsletter, I turn towards an even more influential, but often overlooked group of shareholders: Controlling shareholders.

Many (sustainable) corporate governance measures are constructed against the backdrop of diversified ownership. Yet in most jurisdictions in the world (apart from the ‘Anglo Saxon’ countries) listed companies tend to have one shareholder with enough shares to control the company. In the face of such ‘controlling shareholders’, the power dynamics shift. The presence of a controlling shareholder makes it difficult, if not impossible, for minority shareholders to win an opposing vote in a general meeting. Directors, whose appointment and re-election depends on the controller, have strong incentives to align their decisions with the controlling shareholder’s wishes. The power of corporate control can even transcend the company and affect law, policy and the relationships among nations.

Given these vast powers it seems crucial to ask: Who are these controlling shareholders and what motivates them?

Controlling shareholders are a heterogenous group only united by the fact that they each own a significant stake in a company. They can be founders or families, large individual investors, holding companies or foundations, states or government entities. The list goes on. One prominent archetype is the founder Mark Zuckerberg, CEO and founder of Meta, holds about 57% of voting shares of the company (thanks to Meta’s dual class share structure), making it virtually impossible for minority shareholders to challenge his controversial decision to continuously invest in the metaverse.

Another archetype is family control. Typically evolved out of a founder’s initial stake in the company, the family’s wealth is often tied to the company and family members may be involved as directors, managers or employees. Sometimes these family ties present themselves more indirectly, though a holding company, trust or foundation. I can’t help but be reminded of the fictional Roy family from HBO’s television series Succession, depicting a very cynical and dark take on the family firm. Research suggests the reality of family-controlled companies is thankfully brighter.

So, what drives these shareholders?

Controlling shareholders are typically long-term oriented. This may lead them to consider ESG risks which could affect the long-term value and reputation of their company. They have more power to follow their vision, be more daring than professional managers and bet on innovative technologies crucial for the future. They can persevere even when the stock markets undervalues the company. Given the declining marginal utility of wealth, controlling shareholders may prioritize reputation over additional profits. This might be the case when the family or founder’s name is closely intertwined with the company. Yet, controlling shareholders’ wealth is typically concentrated. This leaves them with fewer incentives to address economy-wide risks such as climate change. We can also imagine some controlling shareholders whose initial objective may be to extract personal wealth from the company; in such cases this runs the risk of an excessive focus on short-term value. The desire to be perceived as responsible or sustainable may furthermore be just as well fulfilled by clever marketing and greenwashing, rather than substantial business decisions.

A number of studies can aid to further outline the specificities of controlling shareholders. A study conducted on Norwegian firms found a profitability premium of family firms, which ‘increases with lower agency conflicts rooted in the family firm’s controlling family, but also with stronger financial constraints caused by limited family wealth, undiversified family wealth, and low liquidity of the family firm’s equity.’ This can lead to underinvestment in the firm. Forthcoming research by Villalonga et al. on ‘corporate ownership and ESG performance’ finds that ownership by founding families or individual investors is negatively associated with ESG performance. This effect is reversed once a family member serves as CEO, in which case companies have the strongest ESG performance. Ownership by government entities or a non-family manager is also positively associated with ESG performance.

Other research explores the incentives that controllers have to reduce negative externalities produced by their controlled company. The authors argue that investments in other companies, which are negatively affected by the controlled company’s externalities, provide an incentive for the controller to reduce those externalities. The more diversified the controller’s wealth, the higher the chances that they will want to reduce externalities. Dual-class shares may be an option for controllers to diversify their wealth while remaining in control, yet in practice this desired effect often fails to materialize.

Ownership by a foundation generally appears to have a positive effect on the long-term orientation of the company. The relationship between control and short-termism is multi-faceted. Long-term oriented controlling shareholders can mitigate short-termism. Strengthening their participation, for example through dual-class or loyalty shares, could enhance this effect. If controlling shareholders are, however, short-termist themselves their presence can have the contrary effect, as they might for example extract wealth through dividend pay-outs to shareholders.

What legal implications can be drawn from this research?

Some existing measures may already stimulate controlling shareholders, such as increased disclosure and reporting obligations imposed on companies or engagement by other investors. It would be interesting to examine how investor engagement in the face of a controlling shareholder can be optimised. Proponents of controlling shareholders’ influence may want to magnify their power with dual-class or loyalty shares. Skeptics on the other hand may fear that this further limits the controller’s accountability and entrench the controller, allowing them to pursue private benefits which are not shared with minority shareholders. Any such measures would need to be carefully balanced with minority protection.

The engagement principles and accountability mechanisms applicable to investors in the form of stewardship codes could serve as an inspiration. Controlling shareholders could be addressed by specific codes tailored to their position, similar to the Singapore Family Stewardship Code, which contains recommendations of values and principles for family-controlled companies. Controlling shareholders may also manifest their commitments through 'relationship agreements’ vis-à-vis the company, as is possible in some jurisdictions.

In the end the incentives guiding controlling shareholders appear as diverse as the group itself, so a one-type-fits-all approach might be counterproductive.

What do you think? Let us know by sharing your thoughts in the poll below.

Cordially yours,

Marleen

MINI POLL...

Q: Should controlling shareholders be incentivized (e.g. with specific stewardship codes or relationship agreements) to be ‘responsible’ owners?

A) Yes, additional codes add transparency, provide guidance and create positive ‘peer-pressure

or

B) No, they would likely only lead to meaningless box-ticking or greenwashing

Marleen Och is a PhD researcher at KU Leuven, Belgium. She works in the field of sustainable finance and corporate governance, writing about shareholder engagement and sustainability.

Please feel free to get in touch, share your thoughts and let us know how we're doing, email Marleen.Och@ecgi.org and follow us on Twitter at @ecgiorg