The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

The Strongest 10%: How Dual-Class Shares Caught on and Why Investors Let Them

Ever since Warren Buffett became the face of successful stock investing, U.S. investors have known that some firms choose to sell stock in more than one category. By issuing "dual-class" shares, some holders, often the founders or founding investors, hold substantially more voting rights than later investors, who take a financial stake that doesn't correspond to their control over the company.

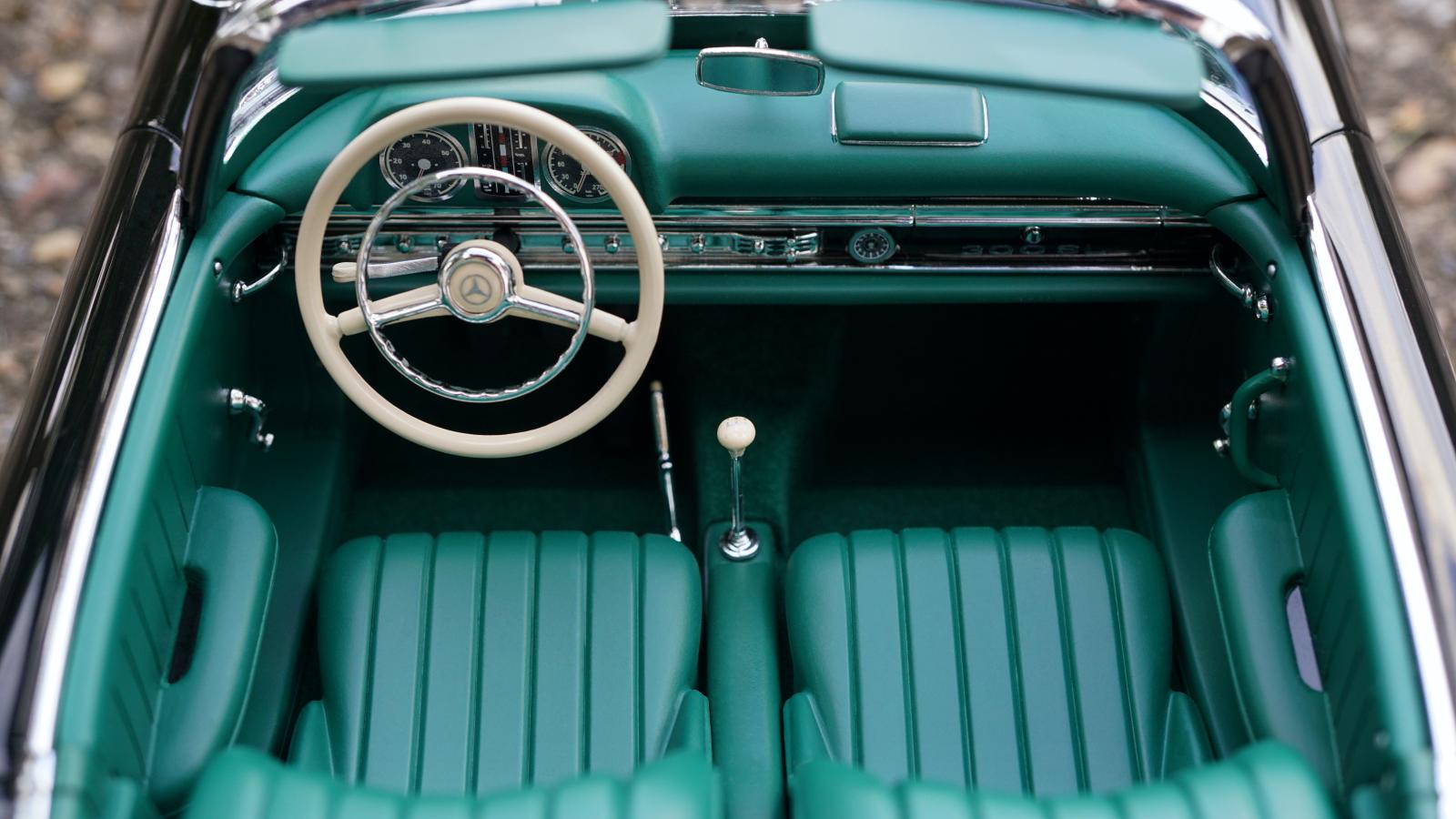

Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway has taken this to an extreme, with A shares holding 10,000 votes for every single vote awarded to a B share, even though they're priced at only 1,500 times as much. More recently, Google's 2004 IPO showed that high-powered technology companies are looking for ways to cash out while allowing founders to stay in charge. Google, now known as Alphabet Inc., offers class A shares worth one vote compared to B shares with 10 votes each and more recently, C shares with no votes. This setup was noteworthy at the time but has since become more and more standard for a certain cohort of initial public offerings.

Big investors and corporate governance advocates tend to oppose these kinds of imbalances. They prefer one share, one vote. Some countries such as the U.K. have enshrined that standard in their financial rules, on the grounds that other structures enable insider trading and give incentives to management that clash with those of the shareholders. Yet the format continues, notably among the same group of IPOs that investors have most clamored to take part in over the last two decades. This shows the tension between setting up safeguards and allowing markets the freedom to find their own way.

"We do want people to be able to contract freely, on the other hand, we do have market failures," said Marco Becht, Executive Director at the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) and Finance Professor at Université libre de Bruxelles. ECGI took a deep dive into whether dual-class share structures make economic sense, as well as whether they serve investors' interests, in an April 17 seminar.

The UK is now debating to join the US in making dual-class share structures more widely available and eligible for listing on the top class of stock exchanges. According to some experts, they should, with specific limitations. Dual-class shares should have a maximum duration of five years, have a weighted voting ratio of no more than 20:1, and holders of the more powerful share class should be required to be directors of the company with strict limits on how they can transfer them, according to recommendations in the March 2021 UK Listings Review chaired by former EU Financial Services Commissioner Lord Jonathan Hill.

Only 38% of dual-class IPOs are "founder firms" with those entrepreneurs still in charge

The mystique of dual-class shares owes a lot to the contemporary sway of the celebrity founder. However, a look at the market shows that only 38% of dual-class IPOs are "founder firms" with those entrepreneurs still in charge, said Michelle Lowry, Finance Professor at Drexel University. It's also hard to make the case that investors are actively seeking out such arrangements given the growing role of passive investment, where retail investors buy funds that represent a broad swath of the market instead of focussing on particular firms.

"As long as these IPOs are effectively guaranteed all of this passive investment, and the percentage of passive investment in the market is going up so much, the incentive they have to adopt or not adopt these structures is just a lot less," Lowry said. This opens the door for managements and boards to choose the structure that is best for them, not necessarily for the rest of the market.

The private benefits that accrue to the controllers can come at a cost to the minority shareholders, said George Dallas, Policy Director of the International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN), whose members are responsible for more than $54 trillion assets under management around the world. For large, informed investors who have a long-term stake in the companies whose stock they buy, diluting their ownership limits their ability to protect their clients.

"Particularly if you're an index-based investor, you're going to be forced to invest in this whether you like it or not, that's the nature of the mandate that the investor has," Dallas said. "Yes, we may need to be concerned about the diktat of the short-term investors, but we may also need to be concerned about the potential diktat of the visionary controlling entrepreneur."

It looks like one size fits most

At least theoretically, the dual-class format is very customizable – companies can choose how many types of shares to offer, whether the split structure is open-ended or has a sunset clause, and how easy it is for founders or other main shareholders to transfer their majority voting stakes. But one of the most striking observations is how an industry standard has evolved in the U.S. for how the levels of control shake out, even though there don't appear to be any particular financial benefits from standardization.

"Most companies choose a similar or identical degree of voting inequality, magnitude and duration. This doesn't look like tailoring, it looks like one size fits most," said Roberto Tallarita, Senior Fellow at Harvard Law School. His research uses a custom database of 211 initial public offerings of non-financial U.S. companies traded on major exchanges from 1996-2018, all using dual-class share structures when heading to the markets.

What he found was that the companies used many different types of contract structures and many different qualitative descriptions of how their companies would work, suggesting that there isn't a common standard for IPO design. Nor did the choices seem to capture an intrinsic ideal structure. However, there was a striking common element of control: nearly two-thirds of companies in the sample, or 64%, chose a structure where the controlling shareholders held only 9% or 10% of the total equity in the company.

One of the main drivers of this ratio seems to be the 10 to 1 difference in voting rights held by the different types of shares, as in the Google IPO. Tallarita said this appears to be an accident of history: dual-class shares were prohibited by the major exchanges from the 1920s to the 1970s, and when they were allowed back in there was a 10:1 cap on voting rights. Regulations loosened further in the 1980s, but the tradition stuck.

Institutional investors generally are open-minded about dual-class shares with a relatively low wedge

A key metric for assessing a dual-class structure is the "wedge" between the level of control and proportion of total equity held by the most influential shareholders. Institutional investors generally are open-minded about dual-class shares with a relatively low wedge between control wielded and stake held, since that may provide some stability and protect against market pressures from short-term speculators. But shares in companies with a high wedge are not popular, Lowry said. In those cases, the interests of the managers and those of their biggest investors are less likely to align.

Deliveroo, the UK food delivery company whose March 31 IPO was widely viewed as a disaster, provided its founder with one of the highest wedges currently in the market: 51%. Chief executive officer Will Shu controls 57% of the votes and only 6% of the stock, said Anete Pajuste, Finance Professor at the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga.

The dual-class shares were only part of the many factors that led investors to question Deliveroo's stock sale. At the same time, its size and reach shows the tradeoff facing policymakers: would the UK be watering down investor protection to make it easier to go public with dual-class shares, or would it be helping London retain its role as one of the world's preeminent financial centers? "This debate about listing rules is closely tied to freedom of establishment and the ability of companies to adopt the company law of their choice," Pajuste said.

Sunset clauses, not required in the US, are a policy tool that could help regulators split the difference. Indefinite control seems to offer diminishing returns. One prominent example is that of Sumner Redstone, who retained control of Viacom long after he was apparently no longer able to manage it. According to Finance Professor Roni Michaely, on a broader scale, dual-class structures seem to stop offering value somewhere between five and ten years after a company goes public.

Making such phase-outs standard could protect "visionary" founders from short-term market pressure to undermine the value of their companies, without giving them unlimited power to preserve control indefinitely, suggested Mike Burkart, Finance Professor at the London School of Economics.

Allowing such structures in some cases encourages firms to broaden their investor base and go public instead of splitting ownership behind the scenes. Hand-selected investors should not be the only ones to participate in the wealth created by the most sought-after high-tech growth firms, and proper regulation can help the markets find a better equilibrium. As Burkart said, "It's not a not 0-1 decision, yes or no, to a dual class share structure. You can choose intermediate solutions."

Rebecca Christie is a non-resident fellow at Bruegel, the Brussels-based think tank.

This article was written as part of the event on "New Listing Rules for SPACs and Dual Class?" on 14 -15 April 2021.

The following article was also published in response to the workshop: SPACs in the middle: IPO shell vehicles are expensive but seem to fill a market niche

-------------------------------------

Event: New Listing Rules for SPACs and Dual Class? (14 - 15 April 2021)

Videos of the presentations are available on the ECGI website and YouTube channel.

Speakers:

- Marco Becht, Professor of Finance, Solvay Brussels School, ULB and ECGI

- Stephane Boujnah, CEO and Chairman of the Managing Board, Euronext

- Mike Burkart, Professor of Finance, London School of Economics (LSE) and ECGI

- Antonio Coletti, Partner, Latham & Watkins

- Luis Correia da Silva, Managing Director, Oxera

- Lora Dimitrova, Senior Lecturer in Finance, University of Exeter

- Luca Enriques, Professor of Corporate Law, University of Oxford and ECGI

- Laura Field, Professor of Finance, University of Delaware and ECGI

- Chris Horton, Partner, Latham & Watkins

- Tim Jenkinson, Professor of Finance, University of Oxford and ECGI

- Michael Klausner, Professor of Business and Professor of Law, Stanford Law School

- Michelle Lowry, Professor of Finance, LeBow School of Business, Drexel University and ECGI

- Roni Michaely, Professor of Finance, Hong Kong University and ECGI

- Jean-Pierre Mustier, Partner Partner, Pegasus Europe

- Anete Pajuste, Professor of Finance, Stockholm School of Economics (Riga) and ECGI

- Lucrezia Reichlin, Professor of Economics, London Business School and ECGI

- Roberto Tallarita, Associate Director and Research Fellow, Harvard Law School