The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

The campaign to free shareholders

Luigi Zingales’ keynote speech on corporate democracy at the SHoF-ECGI Corporate Governance Conference on 27th August 2024, offered a powerful critique of the current state of corporate governance and a radical rethink of how we understand shareholder responsibility.

Zingales kicked off his speech by taking us back to 1970, when Milton Friedman famously argued that the sole responsibility of corporations is to maximize profits. This simple, elegant idea has shaped decades of corporate governance theory and practice. But, as Zingales pointed out, this approach is no longer fit for purpose in a world where corporations wield significant political power. In fact, the world Friedman described—a world where corporations operate within the bounds of law and regulation—has transformed dramatically. As Zingales reminded us, many corporations today are powerful enough to influence, and even change, the rules themselves.

One of the most compelling examples Zingales gave was the case of ExxonMobil. He referenced a shocking recording in which a lobbyist for the oil giant admitted that the company had “aggressively fought against some of the science” around climate change. This wasn’t just a corporate decision to protect their short-term profits—it was a deliberate effort to manipulate public discourse and policy for financial gain. For Exxon, this was simply good business, as it maximized shareholder value. But for the rest of society, it’s a stark reminder of how profit maximization can lead to dangerous and socially harmful behaviors.

Zingales didn’t stop there. He also raised the provocative question of whether private prisons have a fiduciary duty to lobby for longer sentences. After all, their profitability increases with higher incarceration rates. While this sounds absurd on the surface, it highlights a critical flaw in the way we think about corporate responsibility: when the primary goal is maximizing shareholder value, corporations may feel justified—even obligated—to pursue actions that harm society.

Zingales’ proposed solution? We need to move beyond the narrow concept of shareholder value and toward what he calls "shareholder welfare". Shareholders aren’t just profit-hungry investors; they’re people with diverse interests and values. Some may prioritize environmental sustainability, others may care about ethical governance, and many likely don’t want their companies undermining democracy or exploiting loopholes to skirt regulation. Zingales argued that corporations should reflect these broader preferences, not just the financial bottom line.

But how do we do this? How can we ensure that corporations act in the interest of shareholders’ welfare rather than just their financial returns? Zingales suggested an innovative idea: citizen assemblies for corporate governance. Inspired by a concept from political science, this model would see randomly selected shareholders coming together to deliberate on key issues facing a corporation. Instead of expecting every shareholder to vote on complex governance matters, these assemblies would make informed decisions on behalf of the broader shareholder base. It’s a practical way to ensure that shareholders’ voices are heard without overwhelming them with the day-to-day complexities of corporate decision-making.

What was most striking about Zingales’ proposal was its practicality. Corporate democracy doesn’t mean turning every boardroom into a town hall. It’s about giving shareholders a say in how their companies engage with the world, while still recognizing the importance of efficiency and expertise in governance. The idea that shareholders should care about more than just profits—and that they should be able to express those values through corporate governance—is both refreshing and necessary in today’s world.

Zingales ended his speech with a stark warning: if we don’t address the growing disconnect between corporations and the societies they serve, we risk undermining the very foundations of capitalism itself. His call for corporate democracy isn’t just about fairness—it’s about survival. We cannot continue to allow corporations to operate in a vacuum, focused only on short-term profits while ignoring the long-term impacts of their actions on society, the environment, and even democracy.

It is important to reflect on how we, as investors, customers, and citizens, can influence the direction of corporate behavior. The current system may reward profit maximization, but Zingales showed us a glimpse of a better future—one where corporations are guided by the broader welfare of their shareholders and society. It’s a bold vision with endless possibilities.

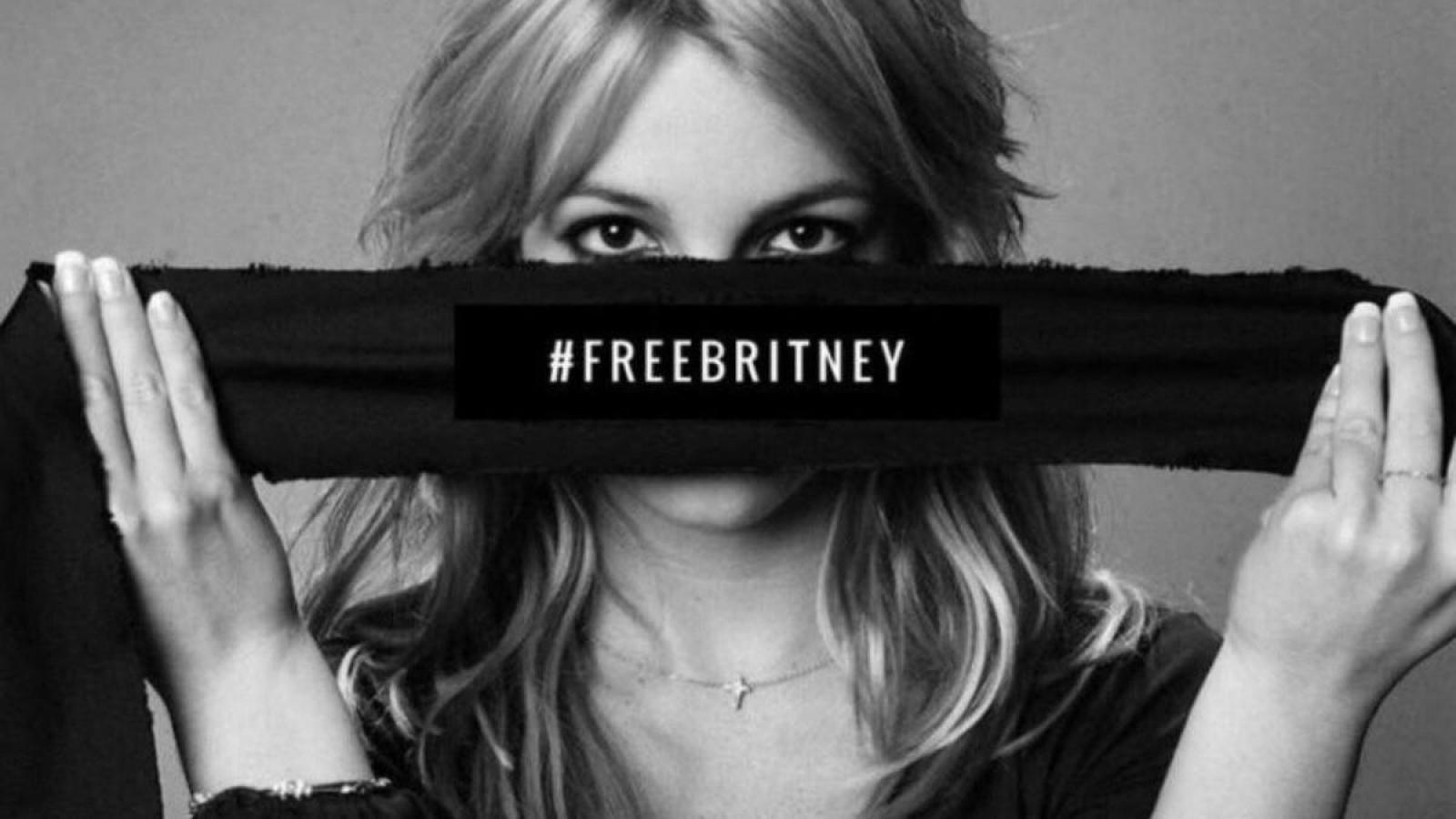

Zingales’ message is clear: the time for corporate democracy is now, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. Later in an interview, Zingales reiterated his message with a call for a campaign to “free shareholders like we freed Britney Spears!”

Directly following this thought-provoking keynote, a panel discussion offered a fascinating dive into the real-world challenges and practicalities of shareholder influence, corporate responsibility, and governance. The panelists brought a wealth of experience, blending academic insight with hands-on corporate governance roles. One of the key points raised was the question of how to balance profit maximization with long-term societal considerations, particularly in cases where corporate actions—such as lobbying or environmental decisions—may conflict with the broader good.

Petra Hedengran, General Counsel at Investor AB, emphasized the importance of long-term value creation through engaged ownership. She argued that sustainability is crucial not just for shareholders but for the longevity of the business itself. Hedengran's defense of long-term shareholder value tied back to Zingales’ challenge: Is long-term value really aligned with societal value, or can corporations hide damaging actions behind a reputation-based facade? Zingales pushed further, pointing out that, historically, firms like IBM and DuPont engaged in ethically questionable activities without suffering significant reputational damage. This led to a broader discussion on corporate accountability, with Mireia Giné suggesting that boards need to face greater scrutiny and responsibility when it comes to meeting shareholders' evolving expectations around social and environmental issues.

The panel highlighted the tension between theoretical ideals and real-world governance challenges. Zingales’ proposal for shareholder assemblies, while innovative, met with practical concerns from panelists, who noted that real-world decisions often blur the lines between value-driven and business-driven choices. For instance, the question of whether firms should divest from controversial markets like Russia brought out differing views on how values and business interests intersect. Ultimately, the panel underscored the complexity of navigating shareholder influence in a world where ethical concerns are becoming increasingly central, yet are often difficult to quantify or prioritize.

_______________

This article is Part One of a five-part blog series covering insights from the SHoF-ECGI Corporate Governance Conference. Explore the rest of the posts: read Part Two here, read Part Three here, read Part Four here, read Part Five here.

Credit: photo via @BritneyHiatus on Twitter