The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

The Battle for Investor Influence

A review of the lecture“Universal Ownership, Systematic Stewardship: Whatever You Call It, Where Do We Stand?” by Professor Madison Condon 5th March 2025.

The role of institutional investors in shaping corporate behavior has never been more contested. The growing influence of universal owners—large, diversified asset managers such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street—has sparked a global debate about whether these firms should actively push for systemic decarbonization or maintain a passive role. In a provocative lecture in the NBS-PRI-ECGI Series, Madison Condon, Associate Professor at Boston University School of Law, dissected the legal, economic, and political dimensions of universal ownership, raising critical questions about investor responsibility, regulatory pushback, and the limitations of financial models in predicting climate risk.

Condon’s research confronted recent challenges to systematic stewardship, which argues that while institutional investors have the incentive to manage climate risks at the portfolio level, significant barriers—including antitrust scrutiny, fiduciary duty constraints, and agency conflicts—limit their ability to act decisively. She pointed to a governance vacuum within universal ownership, where no single investor takes responsibility for corporate oversight, leading to ineffective stewardship and potential greenwashing by firms. Here’s where we stand, and where this debate is headed.

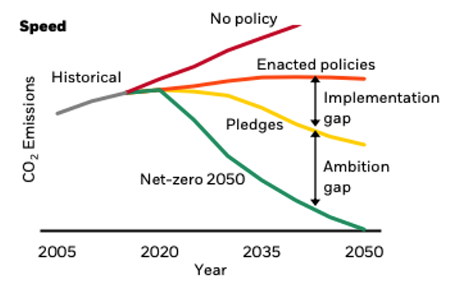

In her seminal paper, Externalities and the Common Owner (2020), Condon outlined how large institutional investors internalize climate externalities because they own broad market portfolios. If one industry—say, fossil fuels—imposes systemic climate damages, those costs spill over into the rest of their holdings. This gives universal owners an incentive to push for sector-wide emissions reductions, even at the expense of individual firm profits. For example, the Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance, a UN-convened initiative, has pressured oil and gas companies like Royal Dutch Shell to adopt stricter decarbonization targets. Similarly, Climate Action 100+, an investor coalition, successfully campaigned for corporate climate disclosures, influencing companies such as ExxonMobil and BP. The logic is straightforward: what’s bad for the planet is bad for diversified investors. While Condon acknowledges that this theory faces several real-world obstacles, she cautions that some obstacles should be taken less seriously than others.

A key portion of Condon’s lecture was dedicated to critiquing mainstream economic models used to assess climate damages. She highlighted serious flaws in the DICE model, developed by Nobel laureate William Nordhaus, which remains the foundation for many corporate and regulatory climate risk assessments. According to Condon, DICE assumes a quadratic relationship between temperature rise and economic damage, meaning it severely underestimates catastrophic risks. It ignores tipping points such as polar ice sheet collapse, freshwater depletion, and feedback loops like permafrost thawing. It focuses on average temperature rise, failing to capture localized extreme weather events—which are what truly devastate economies. One stark example she cited is the Tibetan Plateau water crisis, where melting glaciers could eliminate a vital water supply for nearly two billion people. Yet, economic models largely fail to account for the cascading socio-economic disruptions this would cause. Condon argues that economic climate models need radical reform, incorporating methodologies used in insurance catastrophe models, which better capture tail risks and systemic shocks.

Beyond flawed economic models, financial institutions themselves lack the expertise to properly assess climate risk. Condon highlighted that banks and investment firms do not employ specialists in hydrology, extreme weather, or physical climate risks, leading to a widespread blind spot in long-term asset pricing. She warned that 30-year mortgages, 10-year bonds, and long-term infrastructure projects are being mispriced because financial actors simply do not understand the full scope of climate-related vulnerabilities. This has created what she calls a "ticking time bomb" in financial risk assessment.

Compounding the issue is the increasing reliance on proprietary, opaque climate risk models developed by private firms. Condon raised concerns that these models, which are used by banks, credit rating agencies, and institutional investors, are often neither transparent nor reliable. Many of these risk models are marketed as objective, but in reality, they reflect biased economic assumptions that downplay worst-case climate scenarios. This lack of transparency makes it difficult for regulators, scientists, and investors to critically assess the true financial risks associated with climate change.

Another striking argument from Condon’s lecture is that the financial cost of climate inaction is wildly underestimated. She provided an example of BlackRock’s estimated financial exposure to climate-related losses, which is around $8.2 billion. However, when factoring in the social cost of carbon, the actual climate-related damages from its investments could exceed $900 billion. This staggering discrepancy underscores the misalignment between financial risk modeling and real-world climate harm, highlighting the limits of an investor-led approach to decarbonization without robust regulatory action.

Even if institutional investors wanted to act decisively on climate, could they? Condon discussed several legal constraints that limit their influence. A recent Delaware court ruling in McRitchie v. Zuckerberg (2024) reinforced the principle that corporate directors owe their duty to individual firm profits, not to diversified investors or societal welfare. Condon emphasized, however, that courts will continue to give substantial deference to directors’ decision-making under the business judgment rule. This means that courts are unlikely to find violations of fiduciary duty when reviewing well-informed decarbonization decisions. For example, Microsoft’s substantial investments in carbon capture projects are defensible under this rule, as they align with the company’s broader strategic goals and brand image.

In the U.S., conservative state attorneys general have launched antitrust lawsuits against BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street, accusing them of colluding to limit fossil fuel production. While these claims may not hold up in court, they have already had a chilling effect on investor engagement. Condon noted that European regulators have explicitly permitted ESG collaboration, while the U.S. has moved in the opposite direction, weaponizing antitrust laws to undermine climate action. The stark contrast between the U.S. and Europe suggests that ESG stewardship will become increasingly fragmented across jurisdictions.

Condon emphasized that successful decarbonization requires focusing beyond oil and gas, targeting demand-side transformations in steel, aviation, shipping, trucking, and chemicals. One promising initiative is the First Movers Coalition, where firms like Amazon, Maersk, and Microsoft commit to purchasing low-carbon industrial materials, creating market incentives for clean technology adoption. This supply-chain-driven approach could be more impactful than targeting fossil fuel companies alone. However, it faces antitrust scrutiny, as regulators may view these agreements as anti-competitive collusion rather than market-driven innovation.

Despite these challenges, Condon remains optimistic about the potential for institutional investors to drive change, particularly through localized investments in adaptation measures and green infrastructure. She argued that pension funds and endowments should consider taking a more proactive role in mitigating climate risks, even if it means accepting lower short-term returns to ensure long-term sustainability. Condon highlighted the fiduciary duty of equal treatment, which bars retirement fund trustees from preferencing the needs of near-term beneficiaries over the needs of beneficiaries farther in the future.

Systematic stewardship is at a crossroads. While universal owners have the incentive to act, they face growing political and legal headwinds. The next decade will determine whether investors can drive systemic decarbonization—or whether they will be forced into a defensive, passive role.

-----------------------------------

This lecture is part of the NBS-PRI-ECGI Public Lecture Series, a global initiative on sustainable business. Nanyang Business School (NBS), in collaboration with the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI), launched this series to foster knowledge exchange between academics, practitioners, and policymakers. As part of this initiative, leading academics present cutting-edge research on sustainability topics, while industry experts moderate discussions, providing real-world insights and facilitating dialogue between research and practice.