The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Pollution versus provision markets for the environment, and why it matters

Carbon markets are playing an increasingly important role in climate action. They can take the form of “pollution markets,” where a set of emitting activities in a given jurisdiction must cover their emissions by allowances, which they can buy in a market. The supply of allowances is restricted to meet the climate goals of the jurisdiction. Such emissions trading schemes cover around 18% of global greenhouse emissions today. One example is the EU emissions trading scheme (EU ETS), which is still the largest carbon emissions trading scheme by value.

Alternatively, carbon markets can take the form of voluntary “contribution markets,” where credits from certified projects that reduce emissions or remove carbon are sold to companies or individuals who want to offset their emissions. Many such projects are nature-based, including planting trees and land restoration. Despite the numerous scandals, falling prices and thin liquidity that have plagued the voluntary carbon market, many observers and stakeholders are still bullish about its outlook.

One reason for this optimism is the recent policy developments in the UK and EU, where credits from the voluntary carbon market are being considered for compliance in regulated emissions trading schemes. The UK has indicated its intention to include carbon removals, both nature-based and technology-based, into its emissions trading scheme, the UK ETS. And the EU has recently taken steps to create a new standard for certified carbon dioxide removals from eco-farming practices and industrial processes, with a view to potentially integrating industrial carbon removals in the EU ETS in the future. Integration is likely to boost demand for carbon credits and increase investment in these projects. By pooling more sources of emissions and carbon removals, it will likely also contribute to greater cost-effectiveness of climate action.

There are concerns, however. Opponents to integration point to the mounting evidence documenting that carbon emissions avoided or carbon removals by projects in the voluntary carbon markets are often over-estimated and impermanent. Moreover, many projects would have taken place even without funding, suggesting a lack of additionality. Integrating voluntary credits into regular emissions trading schemes, they argue, would threaten the integrity of emissions trading scheme and encourage greenwashing.

Pollution markets are not the same thing as provision markets

In a recent working paper, we contribute to this debate by arguing that emissions trading schemes and voluntary nature-based carbon markets should remain separate because they pursue different goals: emissions trading schemes aim to reduce emissions from human activities, while nature-based voluntary markets aim to encourage the provision of nature-based emissions carbon removal. Existing Paris-aligned emissions trajectories treat these two goals separately and require both to be met simultaneously.

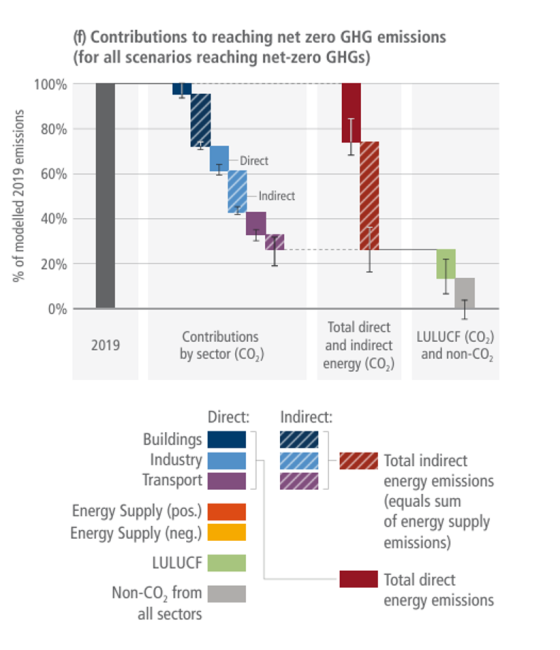

This point is best exemplified in the figure below, which comes from the latest report from the IPCC. The figure shows the contribution of different sectors and sources to reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The bulk of the effort will need to come from emissions reduction in the buildings, industry and transport sector (the black, blue and yellow bars in the second panel, and the red bars in the third panel). About 15% of the effort will additionally come from nature-based carbon removal solutions (the green bar). Voluntary carbon markets are designed to encourage contributions to this green bar. Making such contributions also count towards emissions reduction in the other sectors, as implied by market integration, would amount to double-counting. We need to reduce emissions and increase nature-based carbon removals.

Source: IPCC (2022), AR6, WGIII, Figure T.S. 10.

The figure shows shows the contribution of different sectors and sources to the emissions reductions from a 2019 baseline for reaching net zero GHG emissions. Bars denote the median emissions reductions for all pathways that reach net zero GHG emissions. The whiskers indicate the p5–p95 range. The contributions of the service sectors (transport, buildings, industry) are split into direct (demand-side) as well as indirect (supply-side) CO2 emissions reductions. (Direct emissions represent demand-side emissions due to the fuel use in the respective demand sector. Indirect emissions represent upstream emissions due to industrial processes and energy conversion, transmission and distribution.

Interestingly, the discussion at the EU level about market integration only concerns industrial carbon removals at this stage and thus avoids this double-counting trap. The UK proposal does not.

Should SBTi allow companies to use carbon credits to meet their decarbonization goals ?

These debates are not limited to emissions trading schemes. On April 9, 2024, the Board of Trustees of the Science-based Target Initiative (SBTi), the leading organization supporting companies in their definition of science-aligned decarbonization, created a furore when it opened the door for the use of carbon credits from the voluntary carbon market to meet scope 3 emissions reduction targets (scope 3 emissions are indirect emissions taking place in a company’s value chain). Until then, the organization had staunchly refused to consider carbon credits, despite intense economic and diplomatic pressures. The SBTi is expected to release a draft for its revised Corporate Net-Zero Standard in the Fall.

Critics of the announcement referred to the extensive scientific evidence that most existing carbon credits are unreliable and that allowing for them would ruin SBTi’s reputation as a serious actor of corporate decarbonization. These are of course valid concerns. Our point is that, additionally, nature-based carbon removals are not a substitute to emissions reduction.

A balanced approach is needed

In conclusion, while carbon markets, both pollution and voluntary, are essential tools in the fight against climate change, their integration must be handled with caution. Keeping emissions trading schemes and nature-based voluntary carbon markets separate ensures that we can simultaneously reduce emissions and increase nature-based carbon removals without compromising the integrity of either system. The future of our climate depends on a balanced approach that recognizes and leverages the strengths of both market types.

-------------------------------

By Estelle Cantillon (Université libre de Bruxelles and CEPR) & Aurélie Slechten (Lancaster University Management School).

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.