The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Lessons from government-driven VC investments in Korea: Government-Sponsored VC Funds and Publicly Traded VC Companies

South Korea’s venture capital (‘VC’) ecosystem has flourished due to the government’s robust policies promoting startups. Unlike the US, Korea lacked investor pools willing to invest in unproven startups in the early 2000s. Therefore, the Korean government has encouraged VC investments to diversify the chaebol-concentrated economy. As a result, investments have surged, positioning the Korean VC industry as the fifth largest among OECD countries in 2021 (OECD, 2021). Since the government’s role is key to understanding the Korean VC ecosystem, my new paper analyzes the unique characteristics of VC funds and VC firms in Korea and identifies challenges for further growth.

Growth of VC investments and the Government-Sponsored VC Funds

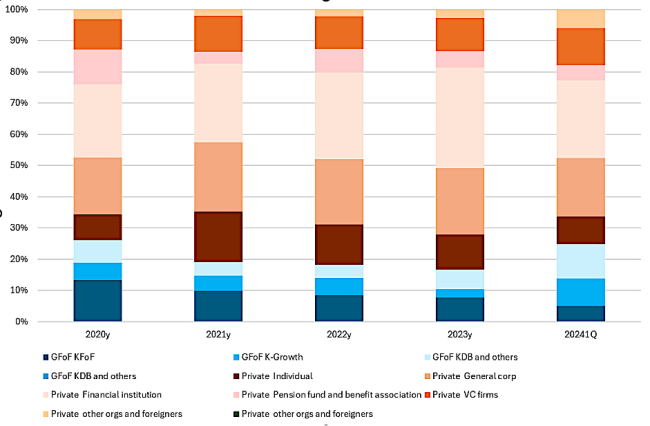

Most VC funds in Korea are government-sponsored funds, whose main investor is the government fund of funds. In response to the shortage of investors willing to invest in VC funds, the government established several funds of funds to bridge the financing gap. The Korea Fund of Funds, formed in 2005 with funding from 13 government ministries, has been pivotal in shaping the VC investment landscape. It has funded approximately 20% of Korea’s total VC funds from 2014 to 2019, significantly contributing to the VC investment ecosystem (Kwak, 2019).

In government-sponsored funds, the power dynamic between the limited partners (‘LPs’) and the general partners (‘GPs’) differs from that of typical VC funds. As opposed to independent VC funds, the fund-formation process of government-sponsored funds is initiated by the government fund of funds rather than by GPs. Although the government funds of funds don’t interfere with the investment decisions of the GPs, they closely monitor the GPs’ investment activities to mitigate moral hazard and agency problems for VC firms (KFoF Guidelines, 2022).

While this structure has been quite effective in mitigating GP agency problems, it also limits GP discretion and autonomy in VC funds, which may reduce the overall returns of VC funds. Since the legal frameworks related to VC funds have been established on the premise of government-sponsored funds as a standard, both the government-sponsored funds and independent VC funds are subject to the same legal frameworks (VIPA, 2023). Regulations for VC funds encompass the mandatory investment ratio, permitted investment instruments, and prohibited activities for VC funds and GPs. Due to these restrictions, some VC firms are compelled to invest in less promising startups that they would not otherwise choose in order to fulfill their investment ratios and avoid sanctions.

Figure 1 Main LPs of Korean VC funds (source: The Ministry of SME and Startups)

Publicly Traded VC firms

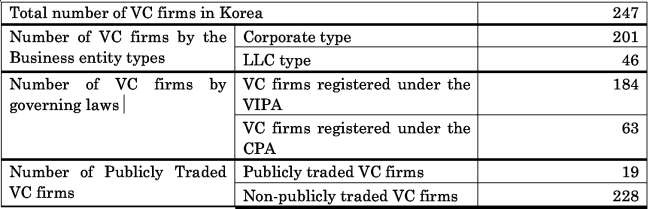

Korean VC firms that serve as GPs of government-sponsored funds are mostly structured as corporations, some of them being publicly traded companies (Kwak, 2021; Song, 2024). Although publicly traded VC firms (‘PTVCs’) account for only 6% of the total number of VC firms, they manage significant assets. The decision of VC firms to go public is related to the development of the Korean VC investment ecosystem through government-sponsored funds supported by government policies. Since public companies are perceived as more trustworthy, PTVCs have a greater chance of being chosen as GPs of government-sponsored funds and attracting other investors.

However, specific conflicts of interest may emerge in PTVCs between VC firm shareholders and VC fund LPs, especially if a fund is underperforming while a VC firm serves as a GP for multiple funds. In this scenario, a VC firm might be tempted to shift its attention from the underperforming fund to a well-performing fund in order to increase the likelihood of earning carried interest, potentially disregarding the interests of the underperforming fund's LPs (Birdthistel& Henderson, 2009).

Investor protection issues may arise due to information asymmetry between VC firms and their investors (Kim, 2017). While PTVCs must adhere to the same disclosure requirements as other listed companies, PTVCs’ business models differ in that their earnings are linked to the performance of the VC funds they manage. Because there are no specific disclosure requirements for PTVCs regarding VC funds, public investors struggle to make informed decisions about them.

[Table 1] Classification of VC firms in Korea (source: KVCA July 2024)

Challenges encountered by Korean VC funds and VC firms

In order to develop VC investment further at the current stage, it is crucial to focus on aligning legal frameworks and policies with entrepreneurial incentives while refining regulations governing VC firms and funds. First, legal frameworks for VC investment should be updated to support this transition by giving GPs more discretion and autonomy in managing their respective funds. For example, legal systems can be reformed to provide varying levels of regulation for government-sponsored funds and independent VC funds while allowing more discretion to GPs in the case of independent VC funds.

Second, regulations governing VC firms as GPs can be revised to strengthen their fiduciary duties when managing conflicting interests among stakeholders. Current rules inadequately address conflict of interest situations, suggesting a need for a revamped regulatory framework that clarifies and enforces VC firms’ duties in managing conflicts fairly.

Finally, regarding PTVCs, stock exchanges should conduct additional reviews of the governance structure of VC firms seeking to go public, focusing on whether they have mechanisms in place to address conflicts between their shareholders and the LPs of their funds. In addition, disclosure frameworks for PTVCs need to be heightened to mitigate information asymmetry by disclosing to investors material information related to the VC funds that these firms manage.

_______________

By Narae Lee (Bliss Law Office)

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.