The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Korea’s shareholder activism – A game-changing transformation since 2022

The year 2022 marked a significant turning point for shareholder activism in Korea. The engagement story of Align Partners, an activist fund, with SM Entertainment, a K-pop producing powerhouse and a listed company, has sparked great public interest. SM Entertainment, named after its founder Mr. Soo-Man Lee, recruited young talents and trained them to become K-pop superstars with the help of experienced producers, songwriters, and vocal and dance coaches. Mr. Lee was praised as a pioneer of the K-Pop business model and the Korean wave phenomenon (Hallyu), describing the recent growing popularity of Korean movies, TV series and pop music.

Beneath this success, SM Entertainment was marred by poor corporate governance. Despite holding only 18.5% of shares, Mr. Lee managed SM Entertainment to outsource production services to his wholly owned company, which received a significant portion of the company's annual profits, sometimes as much as 40%. This "tunneling" practice drew criticism from many shareholders, but the management, under Mr. Lee's influence, refused to terminate the contract, arguing that his consulting services were vital for the company's success.

In early 2022, a surprising development occurred. Align Partners, with a mere 1.1% stake in SM Entertainment, successfully appointed a statutory auditor at the annual general meeting of shareholders. The statutory auditor, according to the Korean Commercial Code, holds the power to audit and review the activities of board members and inspect the company's operations. To ensure the auditor's independence and minimize the controlling shareholders' influence, voting rights of each shareholder are capped at 3% at its election under the Korean laws. Align Partners' proposal received widespread support from other shareholders, including the National Pension Service (NPS) and Norges Bank Investment Management, both the world’s largest pension funds. Proxy advisors such as ISS and the Korean Corporate Governance Institute also favored the proposal. Ultimately, more than 81% of voting rights supported Align Partners, which ultimately led to the termination of the tunneling contract between SM Entertainment and Mr. Lee's company. Subsequently, Mr. Lee sold his shares to Hive, the producer of the famous boy band BTS, and the company is now controlled by Kakao Group, a well-known IT giant.

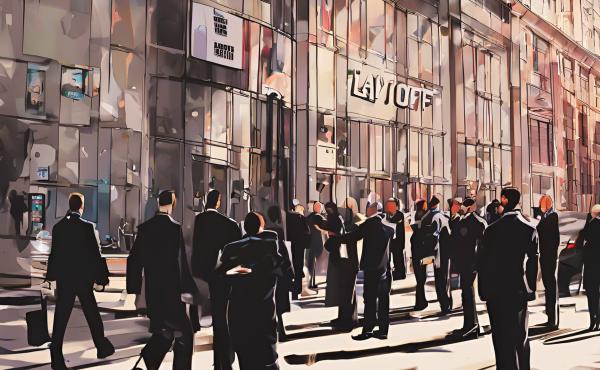

Shareholder activism was once deemed irrelevant for Korean companies, with a few engagements initiated by US hedge funds against large conglomerates (chaebols) proving unsuccessful. The public sentiments against these funds were hostile, criticizing that they focus on short-term investment returns, without considering the long-term interests of the company and development of the Korean economy. The existence of controlling shareholders in most listed companies hindered shareholder activism, and Korean asset managers who had existing business relationships with the chaebols, often supported the controlling parties.

However, the tide shifted with the introduction of the Korean Stewardship Code, making it difficult for asset managers to vote against proposals that clearly promote shareholder value, as their voting policies and results are disclosed. Since its adoption in 2016, more than 200 asset owners and managers, including the NPS, have adhered to the Code. The use of information technology also facilitated proxy voting, with Align Partners employing a fintech app that allowed shareholders to delegate voting rights online without the need of physical delivery of documents. This coincided with a significant increase in retail investors in Korea, from 6.14 million in 2019 to 13.74 million in 2021. The growing number of retail investors made it easier for activists to garner their support, especially for well-known companies like SM Entertainment, similar to the meme stock phenomenon in the US. The surge in retail investors and public interest in corporate governance issues also caught the attention of politicians and government officials, prompting them to address the undervaluation of the Korean stock market, known as the "Korea Discount Problem." As a result, the Financial Services Committee, the financial authority of the Korean government, announced a series of reforms, including the adoption of a mandatory takeover bid rule.

Align Partners' success has inspired other activists, with over ten public companies receiving shareholder proposals from various activist funds during the 2023 annual general meetings. Although only a few of these proposals were accepted – due to the existence of a controlling shareholder in many companies – the trend is expected to continue in the coming years. With the rise of independent hedge fund houses that do not have existing relationships with the chaebols, the challenge over their corporate governance issues is likely to increase. Controlling shareholders have become more open to addressing investors' concerns, exemplified by increased shareholder dividends and stock buybacks.

A more promising aspect is the increasing role of the market in Korean corporate governance. Contrary to LLSV’s observations,[1] Korean corporate and capital market laws offer a comprehensive range of investor protection rights, from preemptive rights to derivative lawsuits against directors. Shareholding requirements for shareholder proposals have been relaxed, and the reappointment of outside directors for more than six years at a particular company has been prohibited to ensure their independence. Despite these efforts, investors have generally been passive in exercising their rights. The rise of shareholder activism is expected to act as a catalyst for investors to actively exercise their various rights stipulated under the laws.

======

By Joon Hyug Chung, an assistant professor at Seoul National University School of Law.

If you would like to read further articles in the 'Corporate Governance in Asia Special Issue' series, click here

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.

[1] LLSV gave two points for Korea in their anti-director index. La Porta, Rafael et al. "Law and finance." Journal of political economy 106.6 (1998), 1131. This was rightly corrected to six points at Spamann, Holger. "The “antidirector rights index” revisited." The Review of Financial Studies 23.2 (2010), 475.