The ECGI blog is kindly supported by

Does sustainable investing work? (Part 1) The three stage rocket analogy

Notwithstanding the recent pushback in the US, the rise of “sustainable investing” (SI) [1] is one of the major trends in the finance industry over the last decade. So we’ll dispense with the statements about how $Xbns are invested in SI funds and investors with AuM of $Ybns are signed up to this that or the other SI initiative, where X and Y are impressively large numbers. You know all that.

What is still slightly confusing is what SI actually means. One of its leading proponents, the UN Principles for Responsible Investment defines it thus (our emphasis)[2]:

Responsible investment involves considering environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues when making investment decisions and influencing companies or assets (known as active ownership or stewardship). It complements traditional financial analysis and portfolio construction techniques.

Responsible investors can have different objectives. Some focus exclusively on financial returns and consider ESG issues that could impact these. Others aim to generate financial returns and to achieve positive outcomes for people and the planet, while avoiding negative ones.

The reality is that this definition conflates two quite different approaches. The first, reflected in the text we have italicized, involves treating ESG factors as potential drivers of risk-adjusted return, and hence sources of alpha. The second, reflected in the text we have highlighted in bold, involves trying to have positive real-world impact through investment activity.

In this article we focus on the second of these. First, because it’s much more interesting. As Alex Edmans of London Business School has highlighted, incorporating ESG factors that are drivers of risk and return isn’t responsible investing – it’s just investing[3]. Second, because it seems to be what many clients think they are getting when they invest in an SI fund, hence the desire in many territories to regulate what funds can use terms such as “responsible” and “sustainable”[4].

So for the purposes of this article, we define SI as: using investing activity to influence companies and assets so as to generate financial returns while achieving positive outcomes for people and the planet, and avoiding negative ones.

This means we are very focused on the real-world impact of SI strategies and activities on relevant environmental and social issues, not their impact on financial performance or risk management. That isn’t to say the latter perspective is not important. Indeed, many proponents of ESG investing claim that it was only ever about ESG risks and impacts on returns. While ESG factors certainly can be important in this way, we would contend that the claims for SI have in many cases gone far beyond this, into impact. And it is this impact dimension that we are interested in here.

Another perspective that we are consciously not considering here is values alignment. Not because it’s not important: it’s very desirable that someone who does not want to make money from gambling / tobacco / pornography / fossil fuels should be able to express that preference by excluding companies undertaking those activities from their investment portfolio. But if the goal is simply values alignment rather than impact, then once that exclusion is achieved, so is the objective – there really is nothing more interesting to say.

Finally, we are not addressing the question of whether (or not) using sustainable investing to achieve impact conflicts with fiduciary duty. That’s an important question. But not one for this article, which is focused instead on the extent to which that impact is, in fact, achieved.

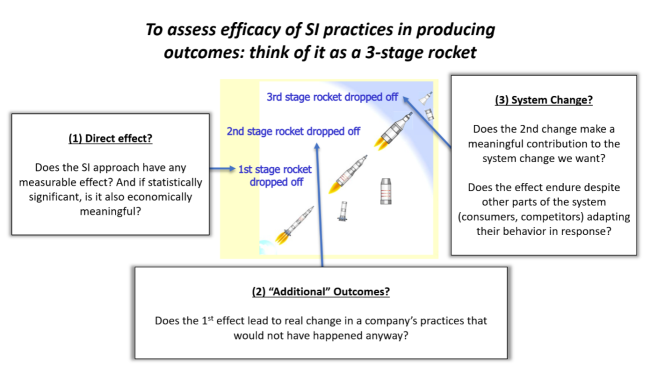

The three-stage rocket

No doubt you are familiar with the concept of a three-stage rocket: a rocket that consists of three parts that each has its own propulsion system. The three stages are all needed, consecutively, to achieve the rocket’s goals: reach orbital speed at the desired height. After the first stage of the rocket has done its work, it drops to the earth; same for the second stage, until only the third, top part of the rocket is left flying. A key insight here is that all 3 stages need to be completed before the launch can be called a success – the third part of the rocket can only achieve the desired height and speed if the first two stages have delivered. At the same time, a launch that fails after the first or second stage can only be called a success during the experimental phase of rocket development.

We argue here that what the investment industry is trying to do with SI is very similar and therefore we’ve started using the 3-stage rocket analogy in a lot of our work and discussions.

In this article we’ll explain the analogy in more detail. In the next two articles (see article links below) we’ll discuss how well the various stages of the SI rocket are working, based on a review of the academic evidence, and what the implications are for SI practitioners.

SI as three-stage rocket

Just like with a three-stage rocket, most SI practices are intended to trigger a three-stage process, all of which need to be completed for the SI intervention to be considered successful:

- First, the activity that the investor undertakes must have some effect on the companies (or the managers of those companies) in which they invest, which (at least in principle) can trigger a change in what the company does. After all, it is companies, acting in the real world, that are the agents of impact.

- Second, managers at the company must indeed respond to that effect and change their actions. This in turn changes what the company does and creates an impact in the real economy that would not have happened without the investor activity.

- Third, the impact in the real economy must persist even after second order impacts and must not be (entirely) unwound by the response of competitors and consumers to the company’s actions.

Let’s take an example of how this might work in theory.

Stage 1: the climate-minded investor invests in green firms and divests from brown firms, with a view to influencing their cost of capital – and the cost of capital changes. It is now higher for brown firms and lower for green firms.

Stage 2: the companies in question, with the understanding that capital is now cheaper or dearer, as the case may be, invest more in green activities and less in brown and, as a result, they reduce their emissions.

Stage 3: adding up the impact on all green and brown companies, at a system- or industry-level overall emissions decline, which contributes to countering climate change.

While the details differ with different SI practices, the high-level principle is often the same: the SI intervention is meant to have some direct effect; that triggers another indirect effect; and that in turn enables some kind of ultimate, systemic effect – something that corrects for externalities or contributes to solving problems.

But the launch mission can abort at any of the three stages. In our example: first the investment and divestment activity may not be significant enough to influence cost of capital to any material degree. Second, managers may not be attuned to small changes in their cost of capital and so even if it does change may not factor this into their investment decision making. Third, the brown activities may simply be taken up by other companies, perhaps in private markets, that do not face the same divestment threat as their listed counterparts.

Academic Research

Now, as with most important things in life – and we would certainly count addressing issues such as climate change, human rights, biodiversity loss etc. amongst them – it is important to make sure our interventions are effective and that we’re focusing our efforts on those interventions that are going to meaningful in the bigger scheme of things. Therefore, we decided to look at the academic record and what it tells us about how much those SI interventions are doing for us – not only judging by their direct effects, but also by their secondary and systemic effects. In other words, judging them across all three stages of the three-stage SI rocket.

We want these articles (see article links below) to be readable summaries for practitioners of our views on the sustainable investing landscape. So we have purposefully not sprinkled these articles with lots of impressive looking academic references. But please be assured that we have done the hard work. We reviewed over 60 relevant papers and publications for the purposes of these articles. We identified these papers from a number of sources. Some we were already familiar with or were recommended by academic SI experts we work with, e.g. from the University of Zurich, London Business School and from the University of St Gallen. Others we identified from reviews of the sustainable investing literature conducted by academic authors. We have published an overview of the process we went through to identify the relevant papers, including a summary of considerations and pitfalls in interpreting them. We think it provides a helpful pathway for practitioners wanting to get into the academic literature in this field. And you can then decide for yourself whether you agree with our conclusions.

Private versus public markets

Much of the evidence we refer to relates to public markets, as this is where there’s the most data! It’s also where there’s the most retail and institutional investing activity, where the marketing efforts of the investment industry are most powerfully deployed, and where regulators have most sway. We readily acknowledge this bias in the analysis, and also acknowledge that Stage 1 and Stage 2 effects are likely to be stronger in private versus public markets for two main reasons. First, private market firms are often involved in raising primary capital and so private market investors are more able to have additional impact (through concessionary capital or higher risk tolerances). Second, private market firms are often closely held, meaning that investors are sometimes in a position where they can more closely direct management action. Nonetheless, private market investors seeking market returns face constraints on impact just as those in public markets do. And delivery of Stage 3 effects are just as difficult in either setting. Nonetheless, private markets do potentially have an impact advantage, and for this reason, a focus on private markets, and in particular through blended finance to facilitate a greater range of bankable projects (particularly in the developing world) is a promising area we return to in our third article. But, for now, our main focus is on public markets.

Overall conclusions

Before discussing some of the details in Parts 2 and 3 of this series, we’d already like to briefly summarize our conclusions. Stage 1 of the rocket works at least to some degree. A number of SI practices can have direct effects (e.g. changes in cost of capital or share prices, and changes to the financial and non-financial incentives faced by corporate managers). However, the effects tend to be relatively small. So while the rocket may get off the stanchion, there’s a risk it may not get much further. Stage 2 of the rocket is temperamental and frequently misfires, causing the rocket to fall back to earth. In particular, there is little evidence that the Stage 1 effects lead to managers of companies changing their behavior, doing more ‘good’ things and less ‘bad’ things at any meaningful scale. Indeed in some cases stage 2 can backfire and lead to more ‘bad’ and less ‘good’. Finally, successful Stage 3 launches remain the subject of little more than rumored sightings. There is hardly any evidence to support the notion that SI practices are resulting in meaningful systemic effects, such as overall emissions decreasing in an industry or companies contributing additionally to SDGs. This does not mean that they are never having such effects – systemic effects are inherently hard to measure. But rockets clearly reaching orbit are rarely seen.

The path ahead

In the following articles we will explore in more detail the two most common SI practices:

- Engagement with investee companies to try to advocate change directly

- Investment / divestment and its variants to try to influence cost of capital and so advocate change indirectly.

Most currently adopted SI practices are flavors of these two.

Our analysis will suggest that engaging with investee companies appears to be the most effective, with the strongest evidence of Stage 1 and Stage 2 impacts. But even here the impacts are often relatively small and focused on actions that are either low cost for the company or even a win-win for sustainability and long-term value creation.

Using investment and divestment to affect cost of capital seems to work at Stage 1 but often falters at Stage 2, other than in some quite specific circumstances, mainly focused around smaller companies, private or venture financing, or genuine impact investment.

What about Stage 3? We will conclude that there is very limited evidence of Stage 3 impacts, which are, after all, the point of it all. In part this reflects the inherent difficulty of measuring systemic effects. But there is also evidence in some cases of competitive market responses undoing what Stage 2 impacts there were. In our final article we will draw out some implications for SI practitioners.

We find the three-stage rocket analogy helpful because it reminds us that all three stages must be completed for investment impact to be achieved. Practitioners, and even academics, often extrapolate from a successful launch that orbit has been achieved. But as many space pioneers will attest, this is often not the case. As we address important societal challenges, we need a laser-like focus on what could get us into orbit and must avoid being distracted by things that may – at best – make a minor contribution.

We hope this series will help investors, and their clients, tell the difference.

--------------------

By Harald Walkate and Tom Gosling

Continue reading in this series...

Part 2 – Launch and reaching the earth’s lower atmosphere

ECGI Blog: Call for Views: Does sustainable investing work?

--------------------

The research that these articles are based on was generously funded by Royal London Group. Falko Paetzold at the University of Zurich and Julian Kölbel at the University of St. Gallen have kindly agreed to review drafts of these articles and have provided us with invaluable input.

[1] In these articles we will mostly use the term “SI” but we might just as well have used sustainable finance, responsible investing, or even impact investing. Some might also use ESG investing, but as this has different interpretations we’ve tried to avoid the term here.

[2] https://www.unpri.org/introductory-guides-to-responsible-investment/what-is-responsible-investment/4780.article

[3] Edmans, Alex (2023), ‘The End of ESG’, Financial Management 52(1), 3-17, available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/fima.12413

[4] Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) and investment labels regime,https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/external-research/sdr-investment-lab, page 2: “in general consumers agreed that sustainable investing is associated with positive impact”; A Large Majority of Retail Clients Want to Invest Sustainably https://2degrees-investing.org/resource/retail-clients-sustainable-investment/: about 2/3 of consumers are interested in sustainable investing and in this group most are drawn to sustainable funds because they believe this allows them to have impact.

The ECGI does not, consistent with its constitutional purpose, have a view or opinion. If you wish to respond to this article, you can submit a blog article or 'letter to the editor' by clicking here.